Table of Contents

Court filing: Yale’s lawyers make surprising claims about the school’s academic freedom promises

In recent court filings, Yale University defends terminating the employment of psychiatry professor Bandy Lee and makes an astounding argument that its promises of academic freedom and freedom of expression are not legally binding. (Albert Pego / Shutterstock.com)

What good are a university’s speech-protective policies when the people in charge won’t enforce them?

That’s just one of the questions being asked after two incidents at Yale University involving high-profile donors and an alumni who sought to exert their influence over matters that are typically left to faculty and administrators.

Last week, history professor Beverly Gage resigned from her position as director of the university’s prestigious Grand Strategy program and accused Yale of failing to protect academic freedom “amid inappropriate efforts by its donors to influence its curriculum and faculty hiring,” according to The New York Times.

Yale President Peter Salovey quickly issued a statement apologizing to Gage and reaffirming the university’s commitment to “free inquiry and academic freedom.” In a subsequent interview with the Yale Daily News, Salovey explained that there are “probably two principles that are really important to honor” at Yale, including “academic freedom to teach and do scholarship in an unfettered way,” which he calls “sacrosanct at the University.”

Salovey’s recent statements on academic freedom are interesting, because just two weeks earlier, lawyers representing Yale filed a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by Bandy Lee, a former untenured professor in the department of psychiatry whose teaching contract was not renewed in 2020 after she publicly criticized Yale alum and attorney Alan Dershowitz, along with his most prominent client, former President Donald Trump. In an email to top administrators, Dershowitz complained that Lee publicly “diagnosed” him as “psychotic,” which he claimed to be a “serious violation of the ethics rules of the American Psychiatric Association.”

Lee disputed these claims and asked for an investigation, but Yale refused and ended her employment over protected speech.

In response to Lee’s lawsuit, Yale’s lawyers went out of their way to disavow the renowned “Woodward report,” which reshaped the university’s academic freedom policies back in 1975, calling it a “statement of principles, not a set of contractual promises,” even though Salovey said in 2014 that “Yale’s policies are quite explicit; they are based on a report authored by the late C. Vann Woodward.”

In short, Yale officials are saying one thing in the court of public opinion — reaffirming decades of promises to protect and uphold free speech and academic freedom — while their lawyers make very different claims in a court of law.

So which is it?

Given the historical importance of the Woodward report at Yale, and the extent to which it influences the university’s academic freedom and free of speech policies, Yale’s claim — that either some or all of the report is not understood to be official Yale policy — is dubious. Indeed, over the years, Yale and its officials have frequently invoked the Woodward report as if it were official policy.

To say differently now is not only an affront to students and faculty who were given explicit and rosy promises about the university’s “unfettered” support of academic freedom and free speech. That retreat also calls into question the promises Yale has made to alumni, donors, and even its accreditors to support, as stated in its mission statement, the “free exchange of ideas.”

What is the ‘Woodward report’?

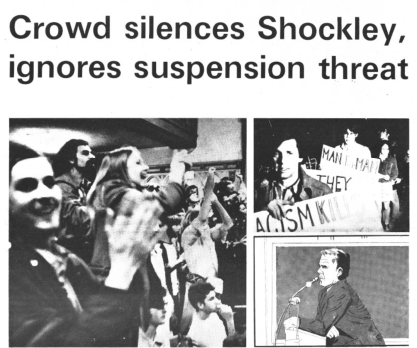

On the evening of April 15, 1974, hundreds of protesters at Yale University converged on Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall, where the controversial scientist William Shockley, an enthusiastic eugenicist, was scheduled to debate conservative magazine publisher William Rusher. Before the event could begin, about 250 protesters, many carrying signs, occupied the auditorium and refused to leave, while hundreds more demonstrated outside. Amid shouts of “Go home, racist!” and “Sterilize Shockley!” — Rusher and Shockley hardly said a word — one Yale official stepped up to the podium and threatened the protesters with suspension.

It didn’t work.

The protests continued for 75 minutes until Yale called the whole thing off. Shockley is quoted in the Yale Daily News calling the event the “worst-handled disruption I’ve experienced.”

Yale was roundly criticized for giving in to the demands of protesters, who sought to shut down an academic debate. The New York Times’ coverage carried the headline, “YALE PROTESTERS SILENCE SHOCKLEY.”

The Shockley incident prompted Yale’s then-president, Kingman Brewster Jr., to call for a review of the university’s policies on academic freedom and free speech. Although Brewster personally thought Shockley’s ideas were “reprehensible” and “unworthy of attention,” he also worried that these types of disruptions — what Henry Kalven had coined the “heckler’s veto” a decade earlier — would have a chilling effect on free speech. He appointed the renowned historian C. Vann Woodward to lead the Committee on Freedom of Expression at Yale. Over the next several months, Woodward and the committee prepared a report for the university’s president and principal governing body, the Yale Corporation.

Known today as the “Woodward report,” its publication in 1975 was a milestone in the free speech movement and laid the foundation for Yale’s academic freedom policies for the next half century. The report affirmed Yale’s commitment to “a free interchange of ideas” and “the fullest degree of intellectual freedom”:

The history of intellectual growth and discovery clearly demonstrates the need for unfettered freedom, the right to think the unthinkable, discuss the unmentionable, and challenge the unchallengeable. To curtail free expression strikes twice at intellectual freedom, for whoever deprives another of the right to state unpopular views necessarily also deprives others of the right to listen to those views.

The report quickly gained “constitutional status” according to Yale’s then-general counsel José Cabranes, and was even printed “in the same format and handsome binding used for the university’s charter and by-laws.”

More importantly, the report was referenced, quoted, and memorialized in Yale policies involving academic freedom and freedom of expression. For Yale to now claim in court that the Woodward report is a mere suggestion denies the unmistakable reality that the report has been and continues to be treated as official policy.

Is the Woodward report official Yale policy?

There’s a very simple reason to conclude that the Woodward report, or at least sections of it, constitute official Yale policy: because language from the report is expressly included in official Yale policies.

The Yale Faculty Handbook section on academic freedom and freedom of expression begins with a direct reference to the Woodward report and quotes from it extensively on the importance of the “free interchange of ideas” and the duty of the university to “do everything possible to ensure within it the fullest degree of intellectual freedom.”

The Woodward report is also memorialized in the Handbook for Instructors of Undergraduates in Yale College:

Freedom of expression is essential to intellectual life, and a classroom is the crucible for the development of intellectual life on a university campus. Yale has long affirmed (in the words of the Woodward Report) “that the primary function of a university is to discover and disseminate knowledge by means of research and teaching” and has therefore developed policies on freedom of expression that carefully balance the listener’s right to conscientious protest with the right of instructors and officially invited speakers to be heard.

Bear in mind that excerpts from the Woodward report are included verbatim in existing Yale policies, indicating that some sections of the Woodward report are indeed enshrined in the school’s official policies.

The free expression statement in the Yale College Undergraduate Regulations begins by noting that the “Yale College Faculty has formally endorsed as an official policy of Yale College the following statement from the Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression at Yale, published in January 1975” [emphasis added]. The statement goes on to quote several paragraphs directly from the Woodward report, including one oft-quoted section:

The primary function of a university is to discover and disseminate knowledge by means of research and teaching. To fulfill this function a free interchange of ideas is necessary not only within its walls but with the world beyond as well. It follows that the university must do everything possible to ensure within it the fullest degree of intellectual freedom.

The list goes on. The Woodward report is referenced and quoted in the statement on free expression in the First-Year Student Handbook, the programs and policies for the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and in the free expression statements for the School of Art, School of Nursing, School of the Environment, and School of Architecture.

Lastly, Guidance Regarding Free Expression and Peaceable Assembly for Students at Yale issued by the Office of the Secretary and Vice President for University Life reads, in part, “Yale is committed to fostering an environment that values the free expression of ideas. In 1975, Yale adopted the Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression at Yale (the Woodward Report) as providing the standard for university policy. This guidance addresses the university’s freedom of expression policy as applied in a variety of situations” [emphasis added].

Excerpts from the Woodward report are included verbatim in existing Yale policies.

For a “statement of principles” that are not “contractual promises,” as Yale’s lawyers argued, the Woodward report curiously seems to be included — by reference, by quotation, and by express adoption — in a wide range of documents intended to make firm commitments. These are not merely philosophical meditations, but institutional policy.

Having made these commitments, is it really so unreasonable that Yale’s faculty and students would rely on them? But if this is how Yale treats its commitments, what good is the word of Yale’s administration on anything else?

When Yale “adopted” the Woodward report

Yale, at a minimum, has adopted portions of the Woodward report as policy by quoting them verbatim in important Yale documents. But what about the report as a whole? Are we to believe Yale’s lawyers when they argue the Woodward Report is merely “a statement of principles”?

Let’s check Yale’s own website. According to the Office of the Secretary and Vice President for University Life — no doubt a credible authority on Yale policy, and likely careful in its choice of words — and with emphasis added: “In 1975, Yale adopted the Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression at Yale (the Woodward Report) as providing the standard for university policy[.]”

But, certainly, if we go back to the era before websites, and perhaps to a more credible authority on Yale policy — say, the trustees of the Yale Corporation — we might discover more about how the report was received. We can’t check all of the records, because the minutes of the Yale Corporation remain sealed for fifty years, which means the 1975 minutes will not be accessible until 2025. However, reporting in The Yale Daily News suggests the Woodward report was favorably received by both the faculty and administration. On March 24, 1975, under the headline “Trustees approve Woodward report,” the student newspaper writes:

This month’s Yale Corporation session featured the approval of the controversial Woodward Committee Report.

[. . .]

The Corporation began discussion of the report at its February meeting, but tabled final consideration until it received more input from various campus faculty groups.

The Corporation gave a general endorsement to the report.

Two weeks later on April 4, 1975, then-president Brewster wrote in an editorial in The Yale Daily News:

I joined without reservation my Corporation colleagues’ endorsement of the general recommendations of the Woodward Report. This includes not only the high value which an academic institution must put on untrammeled freedom of expression, but also the serious disciplinary consequences of any persistent and willful interference with such expression.

News of events at Yale traveled to Massachusetts, where The Harvard Crimson reported on Feb. 4, 1975, that the “Yale College faculty approved the committee’s report on January 16 and sent it on to the Yale Corporation for its action.” A subsequent report noted the Yale Corporation “adopted” the report and quoted assistant law professor Lance M. Liebman, a trustee of the Yale Corporation, who said, “[t]he trustees were of the opinion that even the most unpopular views should be heard at Yale.”

Yale’s approval of the Woodward report was even printed in The New York Times, with an article on Jan. 26, 1975, suggesting the report had been favorably received: “President Brewster, the Daily News and the college faculty have all endorsed it in broad terms, and next month the corporation will pass on it.”

More recently, in the book “Free Speech for Me—but Not for Thee: How the American Left and Right Relentlessly Censor Each Other,” legal historian Nat Hentoff observed that the “Yale Corporation accepted the Woodward report, and in its brief statement alluded—without naming any of those culpable—to past lapses of courage on behalf of free speech.”

The historical record seems abundantly clear that both the board of trustees and faculty voted in favor of resolutions either “endorsing” or “adopting” the Woodward report, and that this positive reception was viewed by both the Yale community and the general public as an endorsement and adoption of the report. Those actions contributed to what faculty and students would reasonably expect from Yale’s commitment to academic freedom. Even if they had not formally adopted it, it has been adopted by practice. Importantly, Yale has benefited from that perception for nearly half of a century, and they’re bailing on it now over a lawsuit brought by a professor that is not likely to threaten its $31 billion endowment.

Yale’s “exemplary policy document”

Even if the intentions of Yale’s president and trustees nearly fifty years ago appear irrelevant, surely Yale has given up the ghost, expressly disclaiming the Woodward report as the relic of a bygone era, right? Well, no. Its current president, Peter Salovey, said in his 2014 address to incoming students (entitled “Free Expression at Yale”) that “it is important on occasions like this one to remind ourselves why unfettered expression is so essential on a university campus. Yale’s policies are quite explicit; they are based on a report authored by the late C. Vann Woodward” [emphasis added].

Salovey — again, the chief executive of the university — has frequently invoked the Woodward report in public remarks, explicitly conveying his understanding that the report is foundational to academic freedom and freedom of speech at Yale. For example, in his 2015 message with Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway, “Affirming our community values,” they wrote:

Forty years ago, explosive debates about race and war divided Yale’s campus, and in response the university formed a core set of principles to support protest and counter-protest. Those principles, available in a document known as the Woodward Report, apply today just as they did then . . . We give the principles in this report our fullest support [emphasis added], and we urge you to read this document.

(“Fullest,” at least, outside of a federal court.)

This was no errant slip of the tongue. In his 2016 “Statement on free speech at Yale,” Salovey said, “Yale’s bedrock commitment to free expression is articulated clearly in the Woodward Report of 1974, which remains our policy today . . . Yale is very much in agreement with this view” [emphasis added].

And in a 2018 statement, “Yale’s commitment to free expression,” the Woodward report was acknowledged as the cornerstone of the university’s academic freedom and freedom of speech policies: “Yale University is committed to the robust testing of ideas through scholarly examination and teaching. We adhere to the principles on free expression set forth in the University’s exemplary policy document, the Report of the Committee on Free Expression at Yale” [emphasis added].

Even if one could argue that specific actions taken by the Yale Corporation in 1975 did not rise to the level of adopting the Woodward report as official policy, that does not appear to be the argument being made by top university officials, at least when doing so publicly suits their needs.

If anything, remarks by Yale’s current president would seem to indicate that the Woodward report is widely thought to be official school policy. Even if it is not, the very fact that the president of the university is regularly saying as much seems problematic for Yale’s motion to dismiss Lee’s lawsuit.

To be sure, Salovey’s public defenses of freedom of expression are welcome and laudable. They should be mirrored by other institutional leaders — too many of whom don’t even bother with a public defense. But those eloquent defenses mean little if Yale’s lawyers say they shouldn’t be taken seriously.

Untenured professors also have rights

The elephant in the room throughout this whole discussion is that the outcome for Bandy Lee would have been much different if she were a tenured professor. Faculty rights to academic freedom and freedom of expression should not depend on whether or not one holds tenure or is on the tenure track; however, in recent years we’ve seen more and more universities violating this principle.

For Yale, its accreditation requires a commitment to academic freedom for all faculty, regardless of rank. The New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE) stipulates accredited institutions are “committed to the free pursuit and dissemination of knowledge” and must assure “faculty and students the freedom to teach and study, to examine all pertinent data, to question assumptions, and to be guided by the evidence of scholarly research.”

Yale’s answer to this requirement is literally the Woodward report. According to a 2019 self study for NECHE accreditation, the school’s statement on freedom of expression explains that “Yale’s policy protecting and celebrating freedom of expression dates to the 1974 Report of the Committee on Free Expression at Yale, chaired by Sterling Professor of History C. Vann Woodward. Freedom of expression includes the ability to protest others’ speech—but neither to prevent it nor prevent it from being heard by others.”

Moreover, the NECHE standards on Teaching, Learning and Scholarship include provisions that each institution “protects and fosters academic freedom for all faculty regardless of rank or term of appointment.”

Faculty rights to academic freedom and freedom of expression should not depend on whether or not one holds tenure.

If anything, Yale’s treatment of its faculty’s academic freedom rights appears to depend a great deal on their “rank or term of appointment.” The main reason Yale was able to rid itself of Lee so easily is because she did not have the protection of tenure and worked on a short-term contract. When one of Yale’s tenured professors receives an apology regarding allegations of improper influence by major donors but an untenured professor loses her job because of improper influence by a prominent alumnus, that tells you everything you need to know about Yale’s promises.

Yale has promises to keep

Yale is a private institution, and is free to privilege other values above free speech and academic freedom, so long as those values are clearly indicated. Some private colleges do just that. Yale, however, makes many explicit promises, both on its website and in its official handbooks, of academic freedom and free speech. It cannot turn back on those obligations when it’s convenient to do so.

Students and faculty may now hesitate to speak out given what happened to Lee. Yale can make all the promises in the world, but when it fails to follow through on keeping those promises and, even worse, instructs attorneys to downplay those promises in a court of law, everyone in the Yale community has cause for concern that they are one bad tweet away from banishment.

What are Yale’s promises worth? If we are to believe its lawyers in court a few weeks ago, they’re not worth that fancy paper the Woodward report is printed on.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

FIRE Statement: X Corp's lawsuit and Texas's investigation into Media Matters for America are deeply misguided

Anonymous speech is as American as apple pie