Table of Contents

Myth-busting reactions to the Supreme Court’s decision in 303 Creative v. Elenis

Jack Gruber / USA TODAY NETWORK

Protesters rally in front of the Supreme Court building on Friday, June 30, 2023, the last day of the term when the Court released opinions on 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, Department of Education v. Brown, and Biden v. Nebraska.

Updated July 17, 2023

Imagine a trans graphic designer in Colorado who wants to expand their business to include creating websites for LGBTQ advocacy organizations. Can the graphic designer be forced to create a website for Moms for Liberty under Colorado’s Anti-Discrimination Act without running afoul of the First Amendment?

Thanks to the Supreme Court’s decision in 303 Creative v. Elenis, the answer is an emphatic, “No.” Of course, 303 Creative involved a Christian graphic artist concerned she would be compelled to create websites celebrating same-sex marriages she does not endorse. But should that factual difference matter when answering the constitutional question of “[w]hether applying a public-accommodation law to compel an artist to speak or stay silent violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment”?

As the six-justice majority correctly recognized, compelling speech violates the Constitution. And it does so whether the government forces “an unwilling Muslim movie director to make a film with a Zionist message” or “an atheist muralist to accept a commission celebrating Evangelical zeal,” as Chief Judge Tymkovich observed in his lone dissent from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit’s ruling.

By the same standard, it would also violate the Constitution if the government compels “a portrait artist to paint a heroic picture of a white supremacist” or compels “a speechwriter to pen an anti-gay screed on behalf of a right-wing politician,” as David French, a former president of FIRE, posed in his New York Times column.

Or to put it as plainly as Justice Gorsuch does in writing for the majority, it violates the Constitution if the government requires “a gay website designer to create websites for a group advocating against same-sex marriages.”

But thanks to the culture wars, what should have been a unanimous decision reaffirming our nation’s commitment to pluralism degenerated into politics as usual. Detractors — and there are lots — have decried the opinion as allowing a new “Jim-Crow-style bigotry.” The Los Angeles Times characterized the decision as “delivering a blow to gay rights” “on the final day of Pride Month.” Even the Wall Street Journal proclaimed that the high court “handed a defeat to gay rights and win to religious conservatives still smarting from the court’s 2015 ruling granting marriage equality to LGBTQ couples.”

This widespread misunderstanding is fueled by the dissent’s mischaracterization of both the facts and the law. Justice Sonia Sotomayor inexplicably claimed that “the Court, for the first time in its history, grants a business open to the public a constitutional right to refuse to serve members of a protected class.” Nothing could be further from the truth.

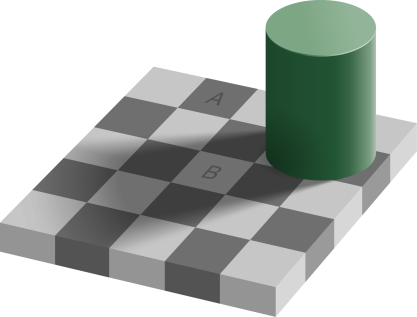

Reading the dissenting opinion — and the past week’s coverage of the decision — one can’t help but think the case is a judicial version of the famous Aldeson checkerboard illusion. The image illustrates how one’s assumptions matter because they affect perception. If a viewer assumes the checkerboard square marked “A” is in the shadow of the cylinder, it appears darker than the “B” square.

But, unlike that illusion, judicial opinions do not rest on assumptions: They rest on facts. And this case was decided on stipulated facts, meaning facts agreed to by the parties litigating the case.

Fact: 303 Creative was not refusing service to gay customers

The website designer, Lorie Smith, was not asking to be allowed to refuse to serve LGBTQ customers. The parties stipulated that Smith was “willing to work with all people regardless of classifications such as race, creed, sexual orientation, and gender.” Further, the parties agreed that Smith “will gladly create custom graphics and websites” for clients of any sexual orientation.

What she was not willing to do, however, was create content that contradicts her belief “that marriage is a union between one man and one woman,” regardless of who orders it.

Fact: 303 Creative’s website designs are a form of expression, which implicates the First Amendment

The parties agreed that Smith’s website designs implicate the First Amendment as they are “expressive” in nature. Her graphics and website designs are “original,” “customized and tailored” through close collaboration with individual couples, and they will “express Smith’s and 303 Creative’s message celebrating and promoting” her view of marriage.

Thus, the decision does not open the door to wanton discrimination in the provision of goods and services. As Justice Gorsuch notes, “Colorado does not just seek to ensure the sale of goods or services on equal terms. It seeks to use its law to compel an individual to create speech she does not believe.”

In the First Amendment context, the mere existence of a law is enough to chill expression, an injury that allows one to sue in federal court.

Contrary to Justice Sotomayor’s characterization, the majority reaffirmed its 2018 statement in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission:

States may “protect gay persons, just as [they] can protect other classes of individuals, in acquiring whatever products and services they choose on the same terms and conditions as are offered to other members of the public. And there are no doubt innumerable goods and services that no one could argue implicate the First Amendment.”

Since the ruling, a judge in Texas is trying to use the 303 Creative opinion to argue she does not have to perform same-sex weddings. But the judge is making a religious liberty claim distinct from the compelled speech claim in 303 Creative.

Moreover, judges presiding over weddings as part of their government duties are acting in their official capacities on behalf of their government employer, which does not receive protection under the First Amendment's free speech clause at all. The state of Texas, as the judge's employer, can control how its employees perform their work, even when it includes speech, without implicating the free speech rights 303 Creative elucidates.

Fact: Smith faced a credible threat of enforcement

After the Tenth Circuit devoted 10 pages to explaining that Smith had standing to sue because she established a credible threat of enforcement if she followed through on her concrete plans to offer wedding website services, “no party challeng[ed] those conclusions” before the Supreme Court. Even the dissent does not dispute that Smith had standing to sue.

But The New Republic and others like Vox Senior Correspondent Illian Millhiser accused Justice Gorsuch of “making false claims” about a case “that does not exist, involving websites that do not exist.” The National Review debunked these misrepresentations. Regardless, from a legal perspective, there is nothing sinister about challenging a law before it is actually enforced.

Indeed, in the First Amendment context, the mere existence of a law is enough to chill expression, an injury that allows one to sue in federal court. In this case, in addition to the chilling effect, state officials or private citizens could bring actions to enforce the law. And penalties include fines of up to $500 per violation, submission of ongoing compliance reports to Colorado officials, and mandatory remedial training.

There was no dispute that Colorado had every intention of enforcing the law. And neither Smith nor others need to endure these kinds of penalties before being able to challenge an unconstitutional law in court.

When read fairly against the facts, the decision should serve as a strong antidote to the culture wars. As both a means and an end, the First Amendment is what enables us to change perceptions in our pluralistic society.

As Justice Gorsuch eloquently observed, “A commitment to speech for only some messages and some persons is no commitment at all.”

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

FIRE Statement: X Corp's lawsuit and Texas's investigation into Media Matters for America are deeply misguided

Anonymous speech is as American as apple pie