Table of Contents

Nobody said defending free speech was easy

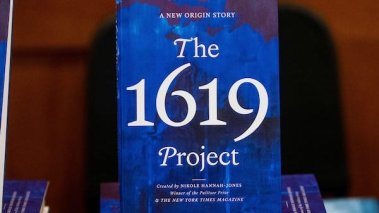

FIRE Summer Intern Emily Orland was disappointed when 1619 Project founder Nikole Hannah-Jones declined to join the journalism program at UNC Chapel Hill. Over the coming months, Emily's experiences as a student reporter taught her some important lessons about free speech. (Michael Caterina / USA Today Network)

I was at my nannying job last summer when I got the Twitter notification: “UNC Board of Trustees Denies Tenure to 1619 Project Author Nikole Hannah-Jones.”

It was the only time the three-year-old boy I cared for heard a curse word slip out of my mouth.

During my first year at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I religiously listened to the 1619 Project podcast on my walk to class. As a history and journalism major, the project encapsulated everything I hoped to accomplish through my own academic and professional work. The project explores the legacy of slavery in the United States, and while some critics contend it makes inaccurate historical claims, many readers and listeners like myself feel it offers an important perspective on our country’s history. When I heard Nikole Hannah-Jones would be joining UNC’s faculty, I wanted to sign up for her classes.

Despite winning a Pulitzer Prize for the 1619 Project, Hannah-Jones was denied tenure by UNC’s board of trustees in what seemed to be a response to the controversy generated by her work. Even when the board reversed its decision later in the summer, Hannah-Jones, understandably, took her talents elsewhere (UNC earned a spot on FIRE’s 10 worst colleges for free speech list because of the way it handled the situation).

The experience left me disheartened and angry at my university’s governance — but it ultimately led me to reckon with some of my complicated beliefs about free speech and academic freedom.

I had no problem defending Hannah-Jones’ right to tenure and the merits of her scholarship. Many of my family and friends felt UNC was in the wrong, and there was widespread support for Hannah-Jones across UNC’s predominantly liberal campus.

But a few months later, as a reporter for the Daily Tar Heel, UNC’s student newspaper, I was assigned to report a story about a history graduate student who taught a course on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The student had posted inflammatory comments on Twitter about Zionists and about the conflict at large a few months prior to the fall semester. In response, several pro-Israel news sources labeled the tweets antisemitic and called for her removal from the teaching position.

This time, the academic on the chopping block did not enjoy widespread support.

While it had been easy for me to profess my support for Hannah-Jones, I had a harder time defending the graduate student’s unpopular speech. As a Jewish student, I run in social circles with peers who can be sensitive about the conflict. Several family members and friends were skeptical when I told them I was writing the article that explained the situation through a lens of academic freedom. I worried that some would label me as complicit in advancing antisemitism, regardless of my personal feelings about her speech. I even called my rabbi, seeking her advice on how to discuss the conflict in a sensitive manner.

When the newspaper promoted the story on social media, commenters shamed the newspaper for omitting the actual tweets. Students I’d shared dinner with at Hillel said the paper would never have written about the situation from an academic freedom perspective if the doctoral student’s tweets had been about any other minority group.

Anticipating this response, I had almost asked my editor to reassign the story to another writer — but my belief in the core arguments for free speech gave me reason to follow through.

I’ve slowly learned that I’d rather have the opportunity to lob tough, critical questions at professors whose ideas I disagree with than to allow those in power to decide who I can or cannot learn from.

One of the most essential tenets of freedom of speech and academic freedom is that we must allow a variety of ideas to compete in pursuit of the truth. In its 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure, the American Association of University Professors explains that institutions of higher education exist to advance the common good, not to advance the interest of an individual teacher or of an institution as a whole.

Attacks on academics come from proponents of all political ideologies. In 2021, students advocated for the University of San Diego to terminate a professor for writing a personal blog endorsing the idea that COVID-19 originated in a lab in Wuhan, China. At Central Connecticut State University, one professor’s colleagues demanded an apology when he wrote a letter in opposition to the 1619 Project.

My blood might still boil when I hear about a professor advancing an idea I consider divisive. I still firmly believe there is a difference between law and ethics, and just because you can say something does not mean you should. I also understand my personal identity makes it easier for me to defend certain types of speech that don’t attack my humanity or self-worth.

But at the end of the day, I understand that I cannot defend Hannah-Jones’ right to academic freedom without defending the doctoral student, too. I’ve slowly learned that I’d rather have the opportunity to lob tough, critical questions at professors whose ideas I disagree with than to allow those in power to decide who I can or cannot learn from.

I hope there is a student who took the Israel-Palestine course this past fall and loved it. And I hope that in the future, if another star journalist is recruited to UNC, the university will uphold its commitment to academic integrity and not deny a learning opportunity to its students. In the meantime, I’ll be keeping a watchful eye on those in power and encouraging other students to do the same.

Emily Orland is a rising senior at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a FIRE summer intern.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

FIRE Statement: X Corp's lawsuit and Texas's investigation into Media Matters for America are deeply misguided

Anonymous speech is as American as apple pie