Table of Contents

Spotlight on Speech Codes 2015

Executive Summary

The U.S. Supreme Court has called America’s colleges and universities “vital centers for the Nation’s intellectual life.” However, the reality today is that many of these institutions severely restrict free speech and open debate. Speech codes—policies prohibiting student and faculty speech that would, outside the bounds of campus, be protected by the First Amendment—have repeatedly been struck down by federal and state courts for decades. Yet they persist, even in the very jurisdictions where they have been ruled unconstitutional. The majority of American colleges and universities maintain speech codes.

FIRE surveyed 437 schools for this report and found that more than 55 percent maintain severely restrictive, “red light” speech codes—policies that clearly and substantially prohibit protected speech. Last year, that figure stood at 58.6 percent; this is the seventh year in a row that the percentage of schools maintaining such policies has declined.

The extent of colleges’ restrictions on free speech varies by state. In Missouri, for example, over 85 percent of schools surveyed received a red light rating. In contrast, two of the best states for free speech in higher education were Virginia and Indiana, where only 31 percent and 25 percent of schools surveyed, respectively, received a red light rating.

Virginia also took legislative action to protect students’ free speech rights in April 2014, when Governor Terry McAuliffe signed a bill into law effectively designating outdoor areas on the Commonwealth’s public college campuses as public forums. Under the law, Virginia’s public universities are prohibited from limiting student expression to tiny “free speech zones” or subjecting students’ expressive activities to unreasonable registration requirements.

Not all of the news is good, however. Unfortunately, as FIRE predicted in last year’s report, the May 2013 federal “blueprint”—the resolution agreement and accompanying findings letter that concluded the Departments of Education and Justice’s joint investigation into the University of Montana’s sexual assault policies and practices—has continued to have a negative effect on campus free speech rights. Although the overall trend is still towards fewer and less restrictive speech codes, this year a number of colleges and universities adopted more restrictive sexual harassment policies using language taken directly from the blueprint. FIRE continues to urge the Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Education to make clear, much like it did in 2003, that its regulations do not require universities to prohibit protected speech. Until OCR makes such a clarification in public documents and announcements, FIRE believes that more universities will adopt unnecessarily and impermissibly restrictive harassment policies.

Moreover, despite the dramatic drop in speech codes over the past seven years, FIRE continues to see an unacceptable number of universities punishing students and faculty members for constitutionally protected speech and expression. It is essential that students, faculty, and free speech advocates remain vigilant not only about campus speech codes but also about the way universities may—even in the absence of a policy that is unconstitutional as written—silence or punish protected speech.

What, then, can be done about the problem of censorship on campus? Public pressure is still perhaps the most powerful weapon against campus censorship, so it is critical that students and faculty understand and be willing to stand up for their rights when those rights are threatened.

At public universities, which are bound by the First Amendment, litigation continues to be another highly successful way to eliminate speech codes. This year, FIRE launched its Stand Up For Speech Litigation Project, a national effort to eliminate unconstitutional speech codes through targeted First Amendment lawsuits. FIRE’s hope is that by imposing a tangible cost for violating First Amendment rights, the project will reset the incentives that currently push colleges towards censoring student and faculty speech. Lawsuits will be filed against public colleges maintaining unconstitutional speech codes in each federal circuit. After each victory by ruling or settlement, FIRE will target another school in the same circuit—sending a message that unless public colleges obey the law, they will be sued.

Overall, supporters of free speech must always remember that universities can rarely defend in public what they try to do in private. Publicizing campus censorship in any way possible—whether at a demonstration, in the newspaper, or even in court—is the best available response. To paraphrase Justice Louis Brandeis, sunlight really is the best of disinfectants.

Methodology

FIRE, the nation's leading student rights organization, surveyed publicly available policies at 333 four-year public institutions and at 104 of the nation’s largest and/or most prestigious private institutions. Our research focuses in particular on public universities because, as explained in detail below, public universities are legally bound to protect students’ right to free speech.

FIRE rates colleges and universities as “red light,” “yellow light,” or “green light” institutions based on how much, if any, protected speech their written policies restrict. FIRE defines these terms as follows:

Red Light: A red light institution is one that has at least one policy that both clearly and substantially restricts freedom of speech, or that bars public access to its speech-related policies by requiring a university login and password for access. A “clear” restriction is one that unambiguously infringes on protected expression. In other words, the threat to free speech at a red light institution is obvious on the face of the policy and does not depend on how the policy is applied. A “substantial” restriction on free speech is one that is broadly applicable to campus expression. For example, a ban on “offensive speech” would be a clear violation (in that it is unambiguous) as well as a substantial violation (in that it covers a great deal of what would be protected expression in the larger society). Such a policy would earn a university a red light.

When a university restricts access to its speech-related policies by requiring a login and password, it denies prospective students and their parents the ability to weigh this crucial information prior to matriculation. At FIRE, we consider this denial to be so deceptive and serious that it alone warrants a red light rating. Fortunately, since FIRE instituted the automatic red light rating for universities that require a password to access speech-related policies, two of the three universities to initially have done so have since unlocked access to those policies. Only one institution—Connecticut College—currently receives a red light rating for this reason.

Yellow Light: A yellow light institution maintains policies that could be interpreted to suppress protected speech or policies that, while clearly restricting freedom of speech, restrict only narrow categories of speech. For example, a policy banning “verbal abuse” has broad applicability and poses a substantial threat to free speech, but it is not a clear violation because “abuse” might refer to unprotected speech, such as threats of violence or genuine harassment. Similarly, while a policy banning “posters promoting alcohol consumption” clearly restricts speech, it is relatively limited in scope. Yellow light policies are typically unconstitutional, and a rating of yellow rather than red in no way means that FIRE condones a university’s restrictions on speech. Rather, it means that in FIRE’s judgment, those restrictions do not clearly and substantially restrict speech in the manner necessary to warrant a red light rating.

Green Light: If FIRE finds that a university’s policies do not seriously threaten campus expression, that college or university receives a green light rating. A green light does not necessarily indicate that a school actively supports free expression; it simply means that the school’s written policies do not pose a serious threat to free speech.

Exempt: When a private university expresses its own values by stating clearly and consistently that it holds a certain set of values above a commitment to freedom of speech, FIRE does not rate that university.[1] Seven surveyed schools are listed as “exempt” in this report.[2]

Findings

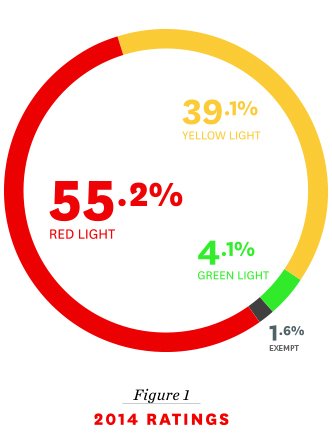

Of the 437 schools reviewed by FIRE, 241 received a red light rating (55.2%), 171 received a yellow light rating (39.1%), and 18 received a green light rating (4.1%). FIRE did not rate seven schools (1.6%).[3] (See Figure 1.)

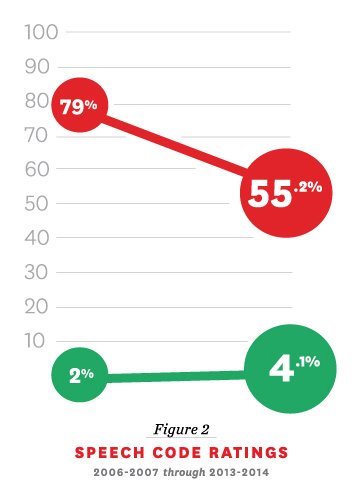

For the seventh year in a row, this represents a decline in the percentage of schools maintaining red light speech codes, down from 58.6% last year and 75% seven years ago. Additionally, the number of green light institutions has more than doubled from eight institutions seven years ago (2%) to 18 this year (3.6%). (See Figure 2.)

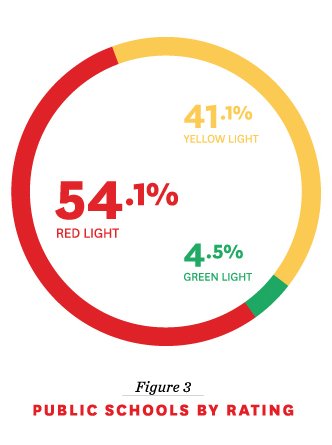

The percentage of public schools with a red light rating also fell for a seventh consecutive year. Seven years ago, 79% of public schools received a red light rating. This year, 54.1% of public schools did—a dramatic change.

FIRE rated 333 public colleges and universities. Of these, 54.1% received a red light rating, 41.4% received a yellow light rating, and 4.5% received a green light rating.[4] (See Figure 3.)

Since public colleges and universities are legally bound to protect their students’ First Amendment rights, any percentage above zero is unacceptable, so much work remains to be done. This ongoing positive trend, however, is encouraging. With continued efforts by free speech advocates on and off campus, we expect this percentage will continue to drop.

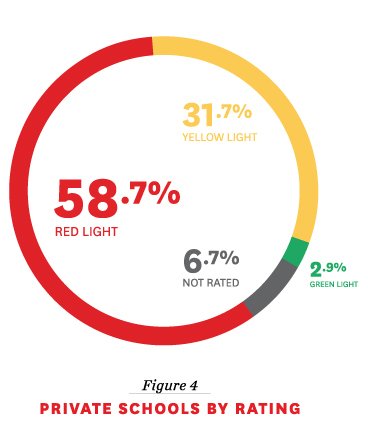

The percentage of private universities earning a red light rating declined almost three percentage points, from 61.5% last year to 58.7% this year. While private universities are generally not legally bound by the First Amendment, most make extensive promises of free speech to their students and faculty. Where such promises are made, speech codes impermissibly violate them.

Of the 104 private colleges and universities reviewed, 58.7% received a red light rating, 31.7% received a yellow light rating, 2.9% received a green light rating, and 6.7% were not rated. (See Figure 4.)

The data showed a wide variation in restrictions on speech among the states.[5] In Missouri, more than 85% of schools surveyed received a red light rating, as did 80% of schools in Washington state and 78% of schools in Louisiana. By contrast, only 25% of the schools surveyed in Indiana received a red light. Other states that fared comparatively well in our survey were Virginia (31% red light) and North Carolina (37% red light).

Virginia is also noteworthy because in April 2014, Governor Terry McAuliffe signed into law a bill effectively prohibiting the establishment of “free speech zones” on Virginia’s public university campuses.[6] The law provides:

Public institutions of higher education shall not impose restrictions on the time, place, and manner of student speech that (i) occurs in the outdoor areas of the institution’s campus and (ii) is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution unless the restrictions (a) are reasonable, (b) are justified without reference to the content of the regulated speech, (c) are narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest, and (d) leave open ample alternative channels for communication of the information.

Given that roughly one in six universities surveyed nationally by FIRE maintains some type of free speech zone,[7] this first-of-its-kind legislation is an important step for free speech on campus, and one that we hope more states will take in the years to come.

Discussion

Speech Codes on Campus: Background and Legal Challenges

Speech codes—university regulations prohibiting expression that would be constitutionally protected in society at large—gained popularity with college administrators in the 1980s and 1990s. As discriminatory barriers to education declined, female and minority enrollment increased. Concerned that these changes would cause tension and that students who finally had full educational access would arrive at institutions only to be offended by other students, college administrators enacted speech codes.

Another likely factor behind the prevalence of speech codes is the over-bureaucratization of American universities. The more college students’ lives are micromanaged by a growing corps of administrators, the more heavily regulated they tend to be, particularly in today’s heavily litigious environment.[8]

No matter how well intentioned, administrators have ignored or at least not fully considered the philosophical, social, and legal ramifications of placing restrictions on speech, particularly at public universities. Federal courts have overturned speech codes at numerous colleges and universities over the past two decades.[9]

Despite the overwhelming weight of legal authority against speech codes, the majority of institutions—including some of those that have been successfully sued—still maintain unconstitutional speech codes.[10] It is with this unfortunate fact in mind that we turn to a more detailed discussion of the ways in which campus speech codes violate individual rights and what can be done to challenge them.

Public Universities vs. Private Universities

The First Amendment prohibits the government—including governmental entities such as state universities—from interfering with the freedom of speech. A good rule of thumb is that if a state law would be declared unconstitutional for violating the First Amendment, a similar regulation at a state college or university is likewise unconstitutional.

The guarantees of the First Amendment generally do not apply to students at private colleges because the First Amendment regulates only government—not private—conduct. Moreover, although acceptance of federal funding does confer some obligations upon private colleges (such as compliance with federal anti-discrimination laws), compliance with the First Amendment is not one of them.

This does not mean, however, that students and faculty at all private schools are not entitled to free expression. In fact, most private universities explicitly promise freedom of speech and academic freedom—presumably to lure students and faculty, since many would not want to study or teach where they could not speak and write freely.

Colby College’s Student Handbook, for example, provides that “[t]he right of free speech and the open exchange of ideas and views are essential, especially in a learning environment, and Colby College upholds these freedoms vigorously.”[11] Similarly, Dickinson College policy states that “College students are both members of the academic community and citizens. As citizens, students should enjoy the same freedom of speech, peaceable assembly, and right of petition that other citizens enjoy.”[12] Yet despite such promises, both of these colleges prohibit a great deal of speech that the First Amendment would protect at a public institution.

At private universities, it is this false advertising—promising free speech and then, by policy and practice, prohibiting free speech—that FIRE considers impermissible. Students may freely choose to enroll at a private institution where they knowingly give up some of their free speech rights in exchange for membership in the university community. But universities may not engage in a bait-and-switch where they advertise themselves as bastions of freedom and then instead deliver censorship and repression.

What exactly is "free speech," and how do universities curtail it?

What does FIRE mean when we say that a university restricts “free speech”? Do people have the right to say absolutely anything, or are only certain types of speech “free”?

Simply put, the overwhelming majority of speech is protected by the First Amendment. Over the years, the Supreme Court has carved out some narrow exceptions to the First Amendment: speech that incites reasonable people to immediate violence; so-called “fighting words” (face-to-face confrontations that lead to physical altercations); harassment; true threats and intimidation; obscenity; and defamation. If the speech in question does not fall within one of these exceptions, it most likely is protected speech.

The exceptions are often wrongly used by universities as justification to punish constitutionally protected speech. There are instances where the written policy at issue may be constitutional—for example, a prohibition on “incitement”—but its application may not be. In other instances, a written policy will purport to be a legitimate ban on something like harassment or threats, but will, either deliberately or through poor drafting, encompass protected speech as well. Therefore, it is important to understand what these narrow exceptions to free speech actually mean in order to recognize when they are being misapplied.

Threats & Intimidation

The Supreme Court has defined “true threats” as only “those statements where the speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals.” Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343, 359 (2003). The Court also has defined “intimidation,” of the type not protected by the First Amendment, as a “type of true threat, where a speaker directs a threat to a person or group of persons with the intent of placing the victim in fear of bodily harm or death.” Id. at 360. Neither term would encompass, for example, a vaguely worded statement that is not directed at anyone in particular.

Nevertheless, universities frequently misapply policies prohibiting threats and intimidation so as to infringe on protected speech.

In January 2014, Colorado State University-Pueblo (CSU-Pueblo) cut off Professor Tim McGettigan’s email access after he sent an email to students and faculty comparing the university administration’s planned layoffs to the Ludlow Massacre, a 1914 incident in which numerous striking Colorado mineworkers and their families were killed. Although McGettigan’s email merely likened the planned terminations to the massacre in terms of its impact on the lives of those affected, the university administration instead treated it as a threat. The president of CSU-Pueblo issued a statement justifying the university’s actions by saying, “Considering the lessons we’ve all learned from Columbine, Virginia Tech, and more recently Arapahoe High School, I can only say that the security of our students, faculty, and staff are our top priority.”[13]

Also in January 2014, Bergen Community College (BCC) in New Jersey placed Professor Francis Schmidt on leave after he posted a supposedly “threatening” picture on Google+. The picture was his seven-year-old daughter doing yoga in a Game of Thrones T-shirt reading “I will take what is mine with fire & blood”—a quote from a well-known character on the popular HBO television show. When Professor Schmidt asked a college security official what the problem was with the photograph, “the security official said that ‘fire’ could be a kind of proxy for ‘AK-47s.’”[14] Moreover, “[BCC President Kaye] Walter said she did not believe that the college had acted unfairly, especially considering that there were three school shootings nationwide in January, prior to Schmidt’s post.”[15] Schmidt retained an attorney, and in late September 2014, BCC expunged the reprimand from Schmidt’s record, stating that “any penalty or restriction” Schmidt suffered is now “rescinded and acknowledged to be null and void.” The letter confirms that Schmidt “will be in good standing with BCC as if the Incident never occurred, and BCC’s records shall so reflect.”[16]

To FIRE, this is a familiar refrain. In recent years, too many universities have censored or punished wholly protected speech by erroneously deeming it “threatening.” In April 2013, for example, the University of Central Florida suspended a professor for making an in-class joke in which he said, of his extremely difficult exam review questions, “Am I on a killing spree or what?”[17] And in September 2011, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Stout was threatened with criminal charges and reported to the university’s “threat assessment team” for two postings hung on his office door. The first was a photo of Nathan Fillion’s character from the television series Firefly along with the following quote from his character: You don’t know me, son, so let me explain this to you once: If I ever kill you, you’ll be awake. You’ll be facing me. And you’ll be armed.” The second posting was a satirical flyer reading, “Warning: Fascism,” hung in response to the university’s overreaction to the Firefly quote.[18]

Incitement

There is also a propensity among universities to restrict speech that offends other students on the basis that it constitutes “incitement.” The basic concept, as administrators too often see it, is that offensive or provocative speech will anger those who disagree with it, perhaps so much that it moves them to violence. While preventing violence is an admirable goal, this is an impermissible misapplication of the incitement doctrine.

Incitement, in the legal sense, does not refer to speech that may lead to violence on the part of those opposed to or angered by it, but rather to speech that will lead those who agree with it to commit immediate violence. In other words, the danger is that certain speech will convince listeners who agree with it to take immediate unlawful action. The paradigmatic example of incitement is a person standing on the steps of a courthouse in front of a torch-wielding mob and urging that mob to burn down the courthouse immediately. To apply the doctrine to an opposing party’s reaction to speech is to convert the doctrine into an impermissible “heckler’s veto,” where violence threatened by those angry about particular speech is used as a reason to censor that speech. As the Supreme Court has said, speech cannot be prohibited because it “might offend a hostile mob” or because it may prove “unpopular with bottle throwers.”[19]

The standard for incitement to violence was announced in the Supreme Court’s decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). There, the Court held that the state may not “forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Id. at 447 (emphasis in original). This is an exacting standard, as evidenced by its application in subsequent cases.

For instance, in Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105 (1973), the Supreme Court held that a man who had loudly stated, “We’ll take the fucking street later” during an anti-war demonstration did not intend to incite or produce immediate lawless action. The Court found that “at worst, it amounted to nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time,” and that the man was therefore not guilty under a state disorderly conduct statute. Id. at 108–09. The fact that the Court ruled in favor of the speaker despite the use of such strong and unequivocal language underscores the narrow construction that has traditionally been given to the incitement doctrine and its requirements of likelihood and immediacy. Nonetheless, college administrations have been all too willing to abuse or ignore this jurisprudence.

Obscenity

The Supreme Court has held that obscene expression, which falls outside of the protection of the First Amendment, must “depict or describe sexual conduct” and must be “limited to works which, taken as a whole, appeal to the prurient interest in sex, which portray sexual conduct in a patently offensive way, and which, taken as a whole, do not have serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15, 24 (1973).

This is a narrow definition applicable only to some highly graphic sexual material; it does not encompass curse words, even though these are often colloquially referred to as “obscenities.” In fact, the Supreme Court has explicitly held that curse words are constitutionally protected. In Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971), the defendant, Paul Robert Cohen, was convicted in California for wearing a jacket bearing the words “Fuck the Draft” in a courthouse. The Supreme Court overturned Cohen’s conviction, holding that the message on his jacket, however vulgar, was protected speech. In Papish v. Board of Curators of the University of Missouri, 410 U.S. 667 (1973), the Court determined that a student newspaper article entitled “Motherfucker Acquitted” was constitutionally protected speech. The Court wrote that “the mere dissemination of ideas—no matter how offensive to good taste—on a state university campus may not be shut off in the name alone of ‘conventions of decency.’” Id. at 670. Nonetheless, many colleges erroneously believe that they may legitimately prohibit profanity and other types of vulgar expression.

Here are just a few examples of such policies from the 2013–2014 academic year:

- At Norfolk State University, the Code of Student Conduct prohibits “profanity by any student on property owned or controlled by the University, or at functions sponsored or supervised by the University.”[20]

- “Profanity” is a violation of the Student Code of Conduct at the University of West Alabama.[21]

Harassment

Harassment, properly defined, is not protected by the First Amendment. In the educational context, the Supreme Court has defined student-on-student harassment as discriminatory, unwelcome conduct “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively bars the victim’s access to an educational opportunity or benefit.” Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, 526 U.S. 629, 633 (1999). This is not simply expression; it is conduct far beyond the dirty joke or “offensive” student newspaper op-ed that is too often deemed “harassment” on today’s college campus. Harassment is extreme and usually repetitive behavior—behavior so serious that it would interfere with a reasonable person’s ability to receive his or her education. For example, in Davis, the conduct found by the Court to be harassment was a months-long pattern of conduct including repeated attempts to touch the victim’s breasts and genitals together with repeated sexually explicit comments directed at and about the victim.

Universities are legally obligated to maintain policies and practices aimed at preventing this type of genuine harassment from happening on their campuses. Unfortunately, they often misinterpret this obligation and prohibit protected speech that is unequivocally not harassment. For example:

- At Colorado State University-Pueblo, “harassment” includes “[t]he infliction of psychological and/or emotional harm upon any member of the University community through any means, including but not limited to e-mail, social media, and other technological forms of communication.”[22]

- At Lehigh University, harassment “occurs when a member of the Lehigh University community or a guest is subjected to unwelcome statements, jokes, gestures, pictures, touching, or other conducts that offend, demean, harass, or intimidate.”[23]

And too often, FIRE sees universities investigate or punish speech that clearly falls well outside the bounds of actual harassment.

In December 2013, Lewis & Clark College found two friends—one black, one white—guilty of harassment for exchanging racially themed inside jokes at a party. A third party overheard the jokes and reported them to campus authorities.

At the November 2013 party, which took place in a campus residence hall, an African-American student jokingly named his beer pong team “Team Nigga” and would exclaim the team’s name when scoring a point. The student also exchanged an “inside joke” greeting with a white friend, who welcomed him by saying, “How about a ‘white power’?” The African-American student then replied in jest, “white power!”[24]

After a third party overheard the comments and reported them to campus authorities, the students were investigated for their “racial and biased comments,” and were ultimately charged with “Physical or Mental Harm,” “Discrimination or Harassment,” and “Disorderly Conduct.” Lewis & Clark found both students guilty on all charges and rejected each of their appeals.[25] In his hearing decision, adjudicator Charlie Ahlquist wrote:

Your repeated use of racially charged language is disruptive and caused the reasonable apprehension of harm in our community. In addition, your initiation of and complicity in using this language in this situation and around campus is unacceptable. Whether intentionally or not, your language has contributed to the creation of a hostile and discriminatory environment.[26]

At the University of Alaska-Fairbanks (UAF), a professor’s complaint over two articles printed in the university’s student newspaper, The Sun Star, led to a months-long investigation of the publication for harassment. The two articles in question were

- A satirical article in the paper’s annual April Fool’s Day issue, which described the university’s plan to construct a vagina-shaped building and included a picture from the 1998 PG-13 rated film Patch Adams.

- An investigative report exploring hateful messages posted to the anonymous “UAF Confessions” Facebook page. The report included screenshots of messages on the page, all of which were publicly available.

Although no disciplinary action was taken against the newspaper, FIRE explained in a letter to UAF why the investigation itself was problematic and impermissible:

The newspaper’s articles are unequivocally protected by the First Amendment and do not meet the legal standard for harassment in the educational setting. By subjecting The Sun Star to further investigation—even after correctly finding the speech to be protected on two separate occasions—UAF has disregarded its binding obligation to uphold the First Amendment on campus. Given the stress and disruption caused by lengthy formal investigations and the ongoing prospect of punishment, UAF students and student journalists will rationally refrain from engaging in protected expression for fear that they will face similarly lengthy investigations and potential discipline at the whim of any offended observer. Chilling speech violates the First Amendment rights of UAF students and cannot be tolerated.[27]

Lakeidra Chavis, then editor-in-chief of the Sun Star, wrote a powerful editorial for the paper about the effect the investigation had on her education: She had been scheduled to take a class with the complaining professor, but she dropped the class after being unable to receive assurances from either the professor or the administration that she would be evaluated in an unbiased manner.[28] Of the incident, Chavis wrote:

If this is the price of Journalism, the price of reporting the truth, of writing satire, of freedom of speech, then it is time to re-evaluate our current expectations, perceptions and understanding of the role of media.

If the price of students voicing their opinions to the dismay of faculty and staff is a limit to our educational rights, it is time for the system to reevaluate its role as a university.[29]

These examples, along with far too many others, demonstrate that colleges and universities often fail to limit themselves to the narrow definition of harassment that is outside the realm of constitutional protection. Instead, they expand the term to prohibit broad categories of speech that do not even approach actual harassment, despite many such policies having been struck down by federal courts.[30] These vague and overly broad harassment policies deprive students and faculty of their free speech rights.

Having discussed the most common ways in which universities misuse the narrow exceptions to free speech to prohibit protected expression, we now turn to the innumerable other types of university regulations that restrict freedom of speech and expression on their face. Such restrictions are generally found in several distinct types of policies.

Anti-Bullying Policies

In recent years, “bullying” has garnered a great deal of media attention, bringing pressure on legislators and school administrators—at both the K–12 and the college levels—to crack down on speech that causes emotional harm to other students. On October 26, 2010, OCR issued a letter on the topic of bullying, reminding educational institutions that they must address actionable harassment, but also acknowledging that “[s]ome conduct alleged to be harassment may implicate the First Amendment rights to free speech or expression.”[31] For such situations, the letter refers readers back to the 2003 “Dear Colleague” letter stating that harassment is conduct that goes far beyond merely offensive speech and expression. However, because it is primarily focused on bullying in the K–12 setting, the letter also urges an in loco parentis[32] approach that is inappropriate in the college setting, where students are overwhelmingly adults.

Under New Jersey’s 2011 Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights Act,[33] speech that does not rise to the level of actionable harassment (or any other type of unprotected speech) is now punishable as “bullying” at public universities in the state. Critically, New Jersey’s language lacks any objective (“reasonable person”) standard, labeling conduct as bullying if it “has the effect of insulting or demeaning any student or group of students.” As a result, students must appraise all of their fellow students’ subjective individual sensitivities before engaging in controversial speech. While the Act does require that there be a “substantial disruption” to the educational environment, it places the onus squarely on the speaker to ensure that his or her speech will not cause another student, however sensitive or unreasonable, to react in a manner that is disruptive to the educational environment (such as by engaging in self-harm or harm to others).

Many of the same flaws plague the Tyler Clementi Higher Education Anti-Harassment Act, a bill that was introduced by Senator Patty Murray and has been included in the Senate Democrats’ first draft of the Higher Education Act, which is currently pending reauthorization. The Act defines harassment, in relevant part, as conduct that is

sufficiently severe, persistent, or pervasive so as to limit a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from a program or activity at an institution of higher education, or to create a hostile or abusive educational environment at an institution of higher education.[34]

Again, because of the lack of an objective, “reasonable person” standard, this formulation conditions the permissibility of speech entirely upon the subjective reaction of the listener—something courts have repeatedly ruled unconstitutional.[35]

Unsurprisingly, with so much attention from federal and state lawmakers, FIRE has seen a dramatic increase in the number of university policies prohibiting bullying. Many universities have addressed the issue by simply adding the term “bullying,” without definition, to their existing speech codes—giving students no notice of what is actually prohibited and potentially threatening protected expression. Yet other policies explicitly restrict protected speech by calling it “bullying” or “cyber-bullying.” Examples of such policies include:

- At the University of West Alabama, “cyberbullying” includes sending “harsh text messages or emails.”[36]

- At McNeese State University, “bullying may be intentional or unintentional,” and “the intention of the alleged bully is irrelevant” when an allegation of bullying is made. Bullying includes “maligning a person or his/her family” as well as “remarks that would be viewed by others in the community as abusive and offensive.”[37]

Policies on Tolerance, Respect, and Civility

Many schools invoke laudable goals like respect and civility to justify policies that violate students’ and faculty members’ free speech rights. While a university has every right to promote a tolerant and respectful atmosphere on campus, a university that claims to respect free speech must not limit speech to only the inoffensive and agreeable.

FIRE has recently seen several instances in which universities have elevated the value of “civility” over the values of free speech and academic freedom. In August 2014, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) revoked the offer of a tenured professorship to Professor Steven Salaita, who was set (to the point that he had already resigned from his job at Virginia Tech) to join UIUC’s American Indian Studies program.[38] The university’s decision was based on a series of controversial Israel-related tweets that Salaita had posted to his personal Twitter account. Several weeks after that decision, UIUC Chancellor Phyllis Wise publicly addressed the Salaita controversy.[39] She wrote:

Some of our faculty are critical of Israel, while others are strong supporters. These debates make us stronger as an institution and force advocates of all viewpoints to confront the arguments and perspectives offered by others. We are a university built on precisely this type of dialogue, discourse and debate.

What we cannot and will not tolerate at the University of Illinois are personal and disrespectful words or actions that demean and abuse either viewpoints themselves or those who express them.

Chancellor Wise went on to emphasize that faculty members must be able to debate in a “civil, thoughtful and mutually respectful manner” and that faculty tenure “brings with it a heavy responsibility to continue the traditions of scholarship and civility upon which our university is built.”

While the mechanics of Salaita’s case are complicated by the fact that his hiring had not yet been finalized at the time of UIUC’s decision, there is no question that the way in which UIUC handled the response will have a chilling effect on the speech of faculty at the university. Indeed, in September, a long list of UIUC faculty signed an open letter to Chancellor Wise protesting the Salaita decision and stating that “[t]he decision…constitutes a dangerous attack on academic freedom which will exert a chilling effect on political speech throughout our campus.”[40]

And in a development that demonstrates just how pervasive the “civility” mantra has become, the chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley used the 50th anniversary of the famous “Free Speech Movement,” which took place on the university’s campus in the 1960s, as the catalyst for an email to the student body about the importance of civility on campus. In an email titled “Civility and Free Speech,” Chancellor Nicholas Dirks cited the Free Speech Movement before writing:

[W]e can only exercise our right to free speech insofar as we feel safe and respected in doing so, and this in turn requires that people treat each other with civility. Simply put, courteousness and respect in words and deeds are basic preconditions to any meaningful exchange of ideas. In this sense, free speech and civility are two sides of a single coin—the coin of open, democratic society.

Dirks’ email continued, “Insofar as we wish to honor the ideal of Free Speech, therefore, we should do so by exercising it graciously.”[41] Dirks’ email was criticized by the Board of Directors of the Free Speech Movement Archives, several of whom faced government retaliation and even arrest for their participation in the movement 50 years ago. The Board’s letter to Dirks stated:

Your statement seems to miss the central point. The struggle of the FSM was all about the right to political advocacy on campus. … It is precisely the right to speech on subjects that are divisive, controversial, and capable of arousing strong feelings that we fought for in 1964 … [W]e are concerned that your call for “civility” may have a chilling effect on the exercise of free speech by Berkeley faculty and students. We therefore encourage you to clarify the intent of your letter while continuing to uphold and affirm the proud traditions established on the Berkeley Campus fifty years ago.[42]

Following this and other criticism, Dirks attempted to walk back his remarks, writing in a follow-up email:

In invoking my hope that commitments to civility and to freedom of speech can complement each other, I did not mean to suggest any constraint on freedom of speech, nor did I mean to compromise in any way our commitment to academic freedom, as defined both by this campus and the American Association of University Professors.[43]

Unsurprisingly, many universities have civility requirements codified in university policy. Here are just two examples of such policies from the 2013–2014 academic year:

- The Evergreen State College has a “social contract” providing that “[c]ivility is not just a word; it must be present in all our interactions.”[44]

- The Student Code of Conduct at Georgetown University prohibits “incivility,” defined as “engaging in behavior, either through language or actions, which disrespects another individual.”[45]

While civility may seem morally uncontroversial, most “uncivil” speech is wholly protected by the First Amendment,[46] and is indeed sometimes of great political and social significance. Much of the expression employed in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s would violate campus civility codes today. Colleges and universities may encourage civility, but public universities—and those private universities that purport to respect students’ fundamental free speech rights—may not require it or threaten mere incivility with disciplinary action.

Internet Usage Policies

A great deal of student expression now takes place online, whether over email or on sites like Facebook and Twitter. Numerous universities maintain policies—many of which were originally written before the Internet became one of students’ primary methods of communication—severely restricting the content of online expression.

Examples of impermissibly restrictive Internet usage policies from the 2013–2014 academic year include the following:

- Athens State University in Alabama prohibits “[c]reating, displaying, transmitting or making accessible threatening, racist, sexist, and offensive, annoying or harassing language and/or material.”[47]

- Boston College prohibits “[t]he use of obscene or intolerant language, and the use of similarly offensive graphic or video images” in electronic communications, and provides that “the determination of what is obscene, offensive, or intolerant is within the sole discretion of the University.”[48]

Policies on Bias and Hate Speech

In recent years, colleges and universities around the country have instituted policies and procedures specifically aimed at eliminating “bias” and “hate speech” on campus. These sets of policies and procedures, frequently termed “Bias Reporting Protocols” or “Bias Incident Protocols,” often include speech codes prohibiting extensive amounts of protected expression. While speech or expression that is based on a speaker’s prejudice may be offensive, it is entirely protected unless it rises to the level of unprotected speech (harassment, threats, and so forth.).

The protocols often also infringe on students’ right to due process, allowing for anonymous reporting that denies students the right to confront their accusers. Moreover, universities are often heavily invested in these bias incident policies, having set up entire regulatory frameworks and response protocols devoted solely to addressing them.

While many bias incident protocols do not include a separate enforcement mechanism, the reality is that the mere threat of a bias investigation will likely be sufficient to chill protected speech on controversial issues. And when the only conduct at issue is constitutionally protected speech, even investigation is inappropriate.

Examples of overly broad bias incident policies from this past academic year include:

- Williams College defines bias incidents as “acts of conduct, speech, or expression that target individuals and groups based on race, religion, ethnic/national origin, gender, gender identity/expression, age, ability, or sexual orientation.” Examples of bias incidents include “telling jokes based on a stereotype,” “making a joke about someone being deaf or hard of hearing, or blind, etc,” making social media posts about someone’s “political affiliations/beliefs,” and “[d]isplaying a sign that is color-coded pink for girls and blue for boys.”[49]

- At Central Michigan University, bias incidents include “expressions of hate or hostility.” Students are urged to report any and all bias incidents, “even those intended as jokes.”[50]

Policies Governing Speakers, Demonstrations, and Rallies

Universities have a right to enact reasonable, narrowly tailored “time, place, and manner” restrictions that prevent demonstrations and speeches from unduly interfering with the educational process. They may not, however, regulate speakers and demonstrations on the basis of content or viewpoint, nor may they maintain college speech regulations which burden substantially more speech than is necessary to maintain an environment conducive to education.

Security Fee Policies

In recent years, FIRE has seen a number of colleges and universities hamper—whether intentionally or just through a misunderstanding of the law—the invitation of controversial speakers by levying additional security costs on the sponsoring student organizations.

The U.S. Supreme Court addressed exactly this issue in Forsyth County v. Nationalist Movement, 505 U.S. 123 (1992), when it struck down a Georgia ordinance that permitted the local government to set varying fees for events based upon how much police protection the event would need. Criticizing the ordinance, the Court wrote that “[t]he fee assessed will depend on the administrator’s measure of the amount of hostility likely to be created by the speech based on its content. Those wishing to express views unpopular with bottle throwers, for example, may have to pay more for their permit.” Id. at 134. Deciding that such a determination required county administrators to “examine the content of the message that is conveyed,” the Court wrote that “[l]isteners’ reaction to speech is not a content-neutral basis for regulation. … Speech cannot be financially burdened, any more than it can be punished or banned, simply because it might offend a hostile mob.” Id. at 134–35 (emphasis added.)

Despite the clarity of the law on this issue, the impermissible use of security fees to burden controversial speech is all too common on university campuses.

In March 2014, Western Michigan University (WMU) informed the Kalamazoo Peace Center (KPC) student group that it could not book a room on campus for a “Peace Week” performance by activist and rapper Boots Riley. KPC came to learn that the university feared disruption because of Riley’s affiliation with the “Occupy” movement. Eventually, WMU relented and agreed to let Riley perform on campus—but only if the student group footed a $62-per-hour bill to have an undercover police officer present at the event. KPC ultimately moved the event off campus to avoid this expense, which it could not afford.[51]

In October 2014, with FIRE’s assistance, KPC filed a civil rights lawsuit against the university alleging that the university’s actions—which ultimately forced the group to hold its event at a “less desirable non-university venue”—were a violation of the group’s First Amendment rights.[52]

WMU was not the only public university this year to disregard the Supreme Court’s decision in Forsyth. In May 2014, Boise State University levied an unconstitutional security fee on a student group for hosting a speech by a gun rights activist.

Boise State’s campus chapter of Young Americans for Liberty was set to hold a speech by Dick Heller, the plaintiff in the U.S. Supreme Court case of District of Columbia v. Heller, the successful Second Amendment challenge to Washington, D.C.’s ban on handguns in the home.[53] Less than 24 hours before the event, a Boise State administrator informed YAL that it would be required to pay $465 in security fees for the presence of five police and security officers and told the group that “Boise State will effectively cancel [the] reservation” if the group did not pay the fees.[54] A university spokesperson later tried to justify the fees by citing the concern “that a community member had been encouraging folks to open carry” in violation of Boise State policy[55]—something YAL had explicitly discouraged among attendees.[56]

As FIRE wrote in a July 2014 letter to the university, the security fee was a violation of the group’s First Amendment rights.

FIRE understands Boise State’s concern that some attending YAL’s event may disobey the university’s policies against firearms on campus, and we recognize that Boise State felt the need to prevent such a possibility. Boise State cannot, however, force student groups to shoulder the cost of security simply due to the possibility that some attendees may choose not to comply with Boise State’s policies by engaging in conduct over which YAL has no control and had, in fact, actively discouraged. Boise State’s policies and practices regarding security for events do not supersede students’ and student organizations’ First Amendment rights.[57]

Following FIRE’s letter, Boise State refunded the security fee.[58]

Prior Restraints

The Supreme Court has held that “[i]t is offensive—not only to the values protected by the First Amendment, but to the very notion of a free society—that in the context of everyday public discourse a citizen must first inform the government of her desire to speak to her neighbors and then obtain a permit to do so.” Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of NY, Inc. v. Village of Stratton, 536 U.S. 150, 165–66 (2002). Yet many colleges and universities do just that, requiring students and student organizations to register their expressive activities well in advance and, often, to obtain administrative approval for those activities.

Here are two such policies from the 2013–2014 academic year:

- At Christopher Newport University in Virginia, “individuals and organizations wishing to exercise their freedom of speech or ‘the right of the People peaceably to assemble’ must register with the Dean of Students at least 24 hours in advance.”[59]

- At Kutztown University of Pennsylvania, “[a]ny group or organization planning to schedule a public demonstration or rally must meet with the Director of Public Safety and Police Services or designee to describe the activity and seek permission.”[60]

Free Speech Zone Policies

Of the 437 schools surveyed for this report, roughly one in six have “free speech zone” policies—policies limiting student demonstrations and other expressive activities to small and/or out-of-the-way areas on campus.[61] Such policies are generally inconsistent with the First Amendment.

In June 2012, in a federal lawsuit brought by a student group seeking to collect signatures on campus for an Ohio ballot initiative, a federal judge held that the University of Cincinnati’s free speech zone policy violated the First Amendment. That policy required all “demonstrations, pickets, and rallies” to be held in a free speech zone comprising just 0.1 percent of the university’s 137-acre West Campus, and required ten days’ advance notice for any expressive activity taking place in the free speech area.[62] Judge Timothy S. Black wrote that

This civil case presents the question, among others, as to whether the University of Cincinnati, a public university, may constitutionally subject speech on its campus, by both students and outsiders alike, to a prior notice and permit scheme and restrict all “demonstrations, picketing, and rallies” to a Free Speech Area which constitutes less than 0.1% of the grounds of the campus. For the reasons stated here, the Court determines that such a scheme violates the First Amendment and cannot stand.[63]

Over the past year, as part of FIRE’s Stand Up For Speech Litigation Project, several students have brought additional federal lawsuits challenging their schools’ free speech zone policies.

In September 2013, Modesto Junior College (MJC) student Robert Van Tuinen was ordered by the college administration to stop handing out copies of the Constitution on Constitution Day because he had not sought prior permission and was not in the college’s small free speech area. After FIRE wrote to MJC asking the college to rescind its unconstitutional policies and received no satisfactory response, Van Tuinen filed a federal lawsuit in October 2013 alleging that the college’s enforcement of its free speech policies violated his First Amendment rights.[64] The college settled the case in February 2014, agreeing to pay Van Tuinen $50,000 and to revise several policies so as to open the campus up to free speech.[65]

Amazingly, Modesto Junior College was not the only school in recent memory to violate students’ First Amendment rights by ordering them to stop distributing copies of the Constitution. In January 2014, members of the student group Young Americans for Liberty (YAL) at the University of Hawaii at Hilo (UH Hilo) were also told to stop handing out Constitutions at an outdoor campus event because they were not in the university’s free speech zone—a small, muddy area comprising just 0.26 percent of the university’s campus at the time.[66]

In April 2014, the president of UH Hilo’s YAL chapter, along with a fellow group member, filed suit in federal court alleging that the university’s actions had violated their First Amendment rights.[67] Although negotiations in that lawsuit are still ongoing as of the time of this report, UH Hilo announced in May that it was implementing an interim policy on speech and expression in the meantime, one that would “permit student speech and assembly without first having to apply for or obtain permission from the university in all areas generally available to students and the community, defined as open areas, sidewalks, streets, or other similar common areas.”[68]

Despite the threat of successful litigation, free speech zones remain common. For example:

- Colorado Mesa University provides students with just one free speech zone: “The concrete patio adjacent to the west door of the University Center.”[69]

- Southern Illinois University Edwardsville “has designated an area within a radius of twenty feet (20’) of ‘The Rock’ in Stratton Quadrangle for on-campus free expression and public demonstration activities.” Activities restricted to the designated area include “any public manifestation of welcome, approval, solicitation, protest, or condemnation,” whether by a group or just an individual. Use of the designated area “must be approved in advance by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Administration.”[70]

What Can Be Done?

The good news is that the types of restrictions discussed in this report can be defeated. A student can be a tremendously effective advocate for change when he or she is aware of First Amendment rights and is willing to engage administrators in defense of them. Public exposure is also critical to defeating speech codes, since universities are often unwilling to defend their speech codes in the face of public criticism.

Unconstitutional policies also can be defeated in court, especially at public universities, where speech codes have been struck down in federal courts across the country. Indeed, this past summer, FIRE launched the Stand Up For Speech Litigation Project, a national effort to eliminate unconstitutional speech codes through targeted First Amendment lawsuits.[71] The lawsuits against Modesto Junior College and the University of Hawaii at Hilo are part of this effort, as are lawsuits against Chicago State University, Citrus College in California, Iowa State University, Ohio University, and Western Michigan University.

The idea behind the Stand Up For Speech Litigation Project is that by imposing a real cost for violating First Amendment rights, the project will reset the incentives that currently push colleges towards censoring student and faculty speech. Lawsuits will be filed against public colleges maintaining unconstitutional speech codes in each federal circuit. After each victory by ruling or settlement, FIRE will target another school in the same circuit—sending a message that unless public colleges obey the law, they will be sued.

Any red light policy in force at a public university is extremely vulnerable to a constitutional challenge. Moreover, as speech codes are consistently defeated in court, administrators are losing virtually any chance of credibly arguing that they are unaware of the law, which means that they can be held personally liable when they are responsible for their schools’ violations of constitutional rights.[72]

The suppression of free speech at American universities is a national scandal. But supporters of liberty should take heart: While many colleges and universities might seem at times to believe that they exist in a vacuum, the truth is that neither our nation’s courts nor its citizens look favorably upon speech codes or other restrictions on basic freedoms.

Spotlight On: The Federal “Blueprint,” One Year Later

In this section of last year’s report, FIRE wrote about the federal “blueprint” letter that concluded the Departments of Education and Justice’s joint investigation into the University of Montana’s (UM’s) alleged mishandling of sexual assault claims. While the allegations against UM concerned only physical assaults, the Departments of Education and Justice proceeded not only to reiterate problematic procedures in sexual assault cases, but also to redefine the boundaries of sexual harassment, which implicates speech as well as conduct.

Specifically, the blueprint urged the adoption of a broad definition of sexual harassment—“any unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature”—and explicitly noted that this definition includes “verbal conduct” (i.e., speech). The blueprint also explicitly stated that allegedly harassing expression need not even be offensive to an “objectively reasonable person of the same gender in the same situation.”

Although the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) backed away from its use of the term “blueprint” in a letter to FIRE (stating that “the agreement in the Montana case represents the resolution of that particular case and not OCR or DOJ policy”),[73] this clarification was never directly communicated by OCR to the many colleges and universities within its jurisdiction. And not surprisingly, many universities—perhaps erroneously believing they were required to do so—have over the past year adopted restrictive sexual harassment policies using language promoted by the blueprint.

Previously, for example, Pennsylvania State University defined sexual harassment as

unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature when: ... such conduct is sufficiently severe or pervasive so as to substantially interfere with the individual’s employment, education or access to University programs, activities and opportunities.[74]

In January 2014, however, the university adopted a new policy with a far broader definition of sexual harassment, one in line with the definition utilized by the blueprint:

Sexual Harassment is defined as unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature that is unwanted, inappropriate, or unconsented to. Any type of Sexual Harassment is prohibited at the University.[75]

Similarly, in June 2014, Georgia Southern University adopted a new policy providing that “[s]exual harassment is defined as unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature.”[76] Prior to June, the university had defined sexual harassment to include only unwelcome conduct that “unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work, living environment, academic performance, or creates an intimidating or hostile work or academic environment.”[77]

For another example, the University of Connecticut used to define sexual harassment as:

any unsolicited and unwanted sexual advance, or any other conduct of a sexual nature whereby ... these actions have the effect of interfering with an individual’s performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive environment.[78]

In December 2013, OCR opened a Title IX investigation into the University of Connecticut following a complaint by several students that the university had failed to respond promptly and effectively to allegations of sexual violence on campus.[79]

The University of Connecticut’s 2013–2014 student code now defines sexual harassment as “any unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature.”[80]

These are just three of many universities that have revised their policies since the blueprint was issued in May 2013. So as much as OCR may say that it did not intend other universities to feel bound by its agreement with the University of Montana, that has in many cases been the agreement’s effect. FIRE expects to see more such revisions until OCR clarifies directly to universities, in no uncertain terms, that sexual harassment does not include all unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature, no matter how isolated or minor that conduct may be.

Appendix A: Schools by Rating

Red Light

Adams State University

Alabama A&M University

Alabama State University

Alcorn State University

American University

Arkansas State University

Armstrong State University

Athens State University

Auburn University

Barnard College

Bates College

Boise State University

Boston College

Boston University

Bridgewater State University

Brooklyn College, City University of New York

Brown University

Bryn Mawr College

Bucknell University

California Institute of Technology

California Maritime Academy

California Polytechnic State University - Pomona

California State University - Channel Islands

California State University - Chico

California State University - Dominguez Hills

California State University - Fresno

California State University - Fullerton

California State University - Los Angeles

California State University - Monterey Bay

California State University - Sacramento

California University of Pennsylvania

Cameron University

Carleton College

Case Western Reserve University

Central Michigan University

Central Washington University

Cheyney University of Pennsylvania

Chicago State University

Christopher Newport University

Clark University

Coastal Carolina University

Colby College

Colgate University

College of the Holy Cross

Colorado College

Colorado Mesa University

Colorado State University - Pueblo

Columbia University

Connecticut College

Davidson College

Delaware State University

Delta State University

DePauw University

Dickinson College

East Carolina University

East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania

East Tennessee State University

Eastern Michigan University

Emory University

Evergreen State College

Florida Gulf Coast University

Florida International University

Florida State University

Fordham University

Fort Lewis College

Franklin & Marshall College

Frostburg State University

Georgetown University

Georgia Institute of Technology

Georgia State University

Gettysburg College

Governors State University

Grambling State University

Grand Valley State University

Harvard University

Howard University

Humboldt State University

Illinois State University

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Iowa State University

Jackson State University

Jacksonville State University

Johns Hopkins University

Kansas State University

Kean University

Keene State College

Kenyon College

Lafayette College

Lake Superior State University

Lehigh University

Lincoln University

Louisiana State University - Baton Rouge

Lyndon State College

Macalester College

Mansfield University of Pennsylvania

Marquette University

Marshall University

McNeese State University

Middle Tennessee State University

Middlebury College

Missouri State University

Missouri University of Science and Technology

Montana State University - Bozeman

Morehead State University

Mount Holyoke College

Murray State University

New College of Florida

New Jersey Institute of Technology

New York University

Nicholls State University

Norfolk State University

North Carolina Central University

Northeastern Illinois University

Northeastern University

Northern Arizona University

Northern Illinois University

Northern Kentucky University

Northwestern Oklahoma State University

Oakland University

Oberlin College

Ohio University

Pennsylvania State University - University Park

Princeton University

Purdue University Calumet

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Rice University

Salem State University

Sam Houston State University

San Francisco State University

Sewanee, The University of the South

Shawnee State University

Smith College

Southeastern Louisiana University

Southern Illinois University at Carbondale

Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville

St. Olaf College

State University of New York - Brockport

State University of New York - Fredonia

State University of New York - New Paltz

State University of New York - Oswego

State University of New York - Plattsburgh

State University Of New York - University at Buffalo

State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry

Stevens Institute of Technology

Swarthmore College

Syracuse University

Tarleton State University

Tennessee State University

Texas A&M University - College Station

Texas Southern University

Texas Woman’s University

The College of New Jersey

The Ohio State University

The University of Virginia’s College at Wise

Troy University

Tufts University

Tulane University

Union College

University of Alabama

University of Alabama at Birmingham

University of Alaska Anchorage

University of California, Merced

University of California, Santa Cruz

University of Central Arkansas

University of Central Florida

University of Central Missouri

University of Cincinnati

University of Connecticut

University of Hawaii at Hilo

University of Houston

University of Idaho

University of Illinois at Chicago

University of Illinois at Springfield

University of Iowa

University of Kansas

University of Louisville

University of Maine - Presque Isle

University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Dartmouth

University of Massachusetts Lowell

University of Miami

University of Michigan - Ann Arbor

University of Minnesota - Morris

University of Minnesota - Twin Cities

University of Missouri - Columbia

University of Missouri - St. Louis

University of Montana

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

University of Nevada, Reno

University of New Hampshire

University of New Mexico

University of New Orleans

University of North Carolina - Greensboro

University of North Carolina School of the Arts

University of North Florida

University of North Texas

University of Northern Colorado

University of Northern Iowa

University of Notre Dame

University of Oregon

University of Richmond

University of South Alabama

University of South Carolina

University of South Florida

University of South Florida at Saint Petersburg

University of Southern Indiana

University of Southern Mississippi

University of Texas at Arlington

University of Texas at Austin

University of Texas at El Paso

University of the Pacific

University of Toledo

University of Tulsa

University of West Alabama

University of West Florida

University of Wisconsin - Green Bay

University of Wisconsin - La Crosse

University of Wisconsin - Oshkosh

University of Wisconsin - Stout

University of Wyoming

Utah State University

Utah Valley University

Valdosta State University

Virginia State University

Wake Forest University

Washington State University

Washington University in St. Louis

Wayne State University

Wellesley College

Wesleyan University

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Western Illinois University

Western Michigan University

Westfield State University

Whitman College

William Paterson University

Williams College

Winona State University

Winston Salem State University

Worcester State University

Wright State University

Youngstown State University

Yellow Light

Amherst College

Angelo State University

Appalachian State University

Auburn University Montgomery

Ball State University

Bard College

Bemidji State University

Binghamton University, State University of New York

Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania

Bowdoin College

Bowling Green State University

Brandeis University

California Polytechnic State University

California State University - Bakersfield

California State University - East Bay

California State University - Long Beach

California State University - Northridge

California State University - San Bernardino

California State University - San Marcos

California State University - Stanislaus

Central Connecticut State University

Centre College

Claremont McKenna College

Clarion University of Pennsylvania

Clemson University

Colorado School of Mines

Colorado State University

Cornell University

Dakota State University

Drexel University

Duke University

Eastern New Mexico University

Edinboro University of Pennsylvania

Elizabeth City State University

Fayetteville State University

Fitchburg State University

Florida A&M University

Florida Atlantic University

Framingham State University

Furman University

George Mason University

George Washington University

Georgia Southern University

Grinnell College

Hamilton College

Harvey Mudd College

Haverford College

Henderson State University

Idaho State University

Indiana State University

Indiana University - Bloomington

Indiana University - Kokomo

Indiana University - Purdue University Columbus

Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne

Indiana University - Purdue University Indianapolis

Indiana University South Bend

Indiana University, East

Indiana University, Northwest

Indiana University, Southeast

James Madison University

Kentucky State University

Kutztown University of Pennsylvania

Lewis-Clark State College

Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania

Longwood University

Louisiana Tech University

Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Metropolitan State University

Miami University of Ohio

Michigan State University

Michigan Technological University

Millersville University of Pennsylvania

Montana Tech of the University of Montana

Montclair State University

New Mexico State University

North Carolina A&T State University

North Carolina State University - Raleigh

North Dakota State University

Northern Michigan University

Northwestern State University

Northwestern University

Occidental College

Oklahoma State University - Stillwater

Old Dominion University

Pitzer College

Pomona College

Purdue University

Radford University

Reed College

Rhode Island College

Richard Stockton College of New Jersey

Rogers State University

Rutgers University - New Brunswick

Saginaw Valley State University

Saint Cloud State University

San Diego State University

San Jose State University

Scripps College

Skidmore College

Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania

Sonoma State University

South Dakota State University

Southern Methodist University

Southwest Minnesota State University

Stanford University

State University of New York - Albany

State University of New York - Brockport

Stony Brook University

Temple University

Texas State University - San Marcos

Texas Tech University

The City College of New York

Towson University

Trinity College

University of Alabama in Huntsville

University of Alaska Fairbanks

University of Alaska Southeast

University of Arizona

University of Arkansas - Fayetteville

University of California, Riverside

University of California, Berkeley

University of California, Davis

University of California, Irvine

University of California, Los Angeles

University of California, San Diego

University of California, Santa Barbara

University of Chicago

University of Colorado at Boulder

University of Delaware

University of Denver

University of Georgia

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

University of Kentucky

University of Maine

University of Maine at Fort Kent

University of Mary Washington

University of Maryland - College Park

University of Montana - Western

University of Montevallo

University of North Alabama

University of North Carolina - Asheville

University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill

University of North Carolina - Charlotte

University of North Carolina - Pembroke

University of North Carolina - Wilmington

University of North Dakota

University of Oklahoma

University of Pittsburgh

University of Rhode Island

University of Rochester

University of South Dakota

University of Southern California

University of Southern Maine

University of Texas at San Antonio

University of Vermont

University of Washington

University of West Georgia

University of Wisconsin - Eau Clair

University of Wisconsin - Madison

Vanderbilt University

Virginia Commonwealth University

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Washington and Lee University

West Virginia University

Western Carolina University

Western Kentucky University

Western Oregon University

Western State College of Colorado

Wichita State University

Yale University

Green Light

Arizona State University

Black Hills State University

Carnegie Mellon University

Cleveland State University

Dartmouth College

Eastern Kentucky University

Mississippi State University

Oregon State University

Plymouth State University

Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania

The College of William & Mary

University of Florida

University of Mississippi

University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Pennsylvania

University of Tennessee - Knoxville

University of Utah

University of Virginia

Exempt

Baylor University

Brigham Young University

Pepperdine University

Saint Louis University

Vassar College

Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Yeshiva University

Appendix B: Rating Changes, 2013–2014 Academic Year

| School Name | 2012–2013 Rating | 2013–2014 Rating |

| Brandeis University | Red | Yellow |

| California State University Long Beach | Red | Yellow |

| California State University Stanislaus | Red | Yellow |

| Central Connecticut State University | Red | Yellow |

| Centre College | Red | Yellow |

| Colorado Mesa University | Yellow | Red |

| Cornell University | Red | Yellow |

| Indiana State University | Red | Yellow |

| Longwood University | Red | Yellow |

| Montana Tech | Red | Yellow |

| Pennsylvania State University | Yellow | Red |

| Plymouth State University | Yellow | Green |

| Purdue University | Red | Yellow |

| Southwest Minnesota State University | Red | Yellow |

| Texas Tech University | Red | Yellow |

| Trinity College | Red | Yellow |

| University of Alaska Southeast | Yellow | Red |

| University of California Irvine | Red | Yellow |

| University of California Merced | Yellow | Red |

| University of California San Diego | Red | Yellow |

| University of Central Florida | Yellow | Red |

| University of Central Missouri | Yellow | Red |

| University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign | Red | Yellow |

| University of Montana Western | Red | Yellow |

| University of North Dakota | Red | Yellow |

| University of West Alabama | Yellow | Red |

| University of Wisconsin Eau Claire | Red | Yellow |

| University of Wisconsin Madison | Red | Yellow |

| Virginia Commonwealth University | Red | Yellow |

| West Virginia University | Red | Yellow |

| Western Kentucky University | Red | Yellow |

| Williams College | Yellow | Red |

Appendix C: State-by-State Information

| State | No. of Schools Rated | Red | Yellow | Green | Exempt |

| Alabama | 14 | 10 | 4 | -- | -- |

| California | 43 | 16 | 26 | -- | 1 |

| Colorado | 11 | 6 | 5 | -- | -- |

| Connecticut | 6 | 3 | 3 | -- | -- |

| Florida | 13 | 10 | 2 | 1 | -- |