Table of Contents

Spotlight on Due Process 2020-2021

Research & Learn

Executive Summary

Thanks to recently adopted federal regulations, students in Title IX hearings now have much improved due process rights. Colleges and universities across the country, however, continue to fail to afford their students due process and fundamental fairness in other disciplinary proceedings. The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education’s (FIRE’s) research reveals that institutions nationwide are refusing to implement a single, fair disciplinary process for all students, instead going to absurd lengths to restrict their rights. Colleges and universities investigate and punish offenses ranging from vandalism to felonious acts of sexual assault, handling many allegations that are arguably better left to law enforcement. But their willingness to administer what is effectively a shadow justice system has not been accompanied by a willingness to provide even the most basic procedural protections necessary to fairly adjudicate accusations of serious wrongdoing. That’s why lawmakers and courts must require colleges to afford their students these protections once and for all.

On August 14, 2020, new federal regulations from the Department of Education took effect, reforming how institutions must handle sexual misconduct complaints under Title IX, the federal law prohibiting sex discrimination in federally funded educational programs. The new regulations, which apply to nearly every college and university in the country, public or private, carefully balance the rights of complainants and accused students alike. They mandate that institutions provide robust procedural protections to students involved in Title IX disciplinary processes, including many that FIRE uses as measurement criteria in this report. This is an obvious change for the better in terms of due process.

Yet our research revealed that while institutions did indeed adopt Title IX policies with comparatively robust safeguards, procedures governing other accusations — including serious or violent acts such as physical attacks, theft, destruction of property, and sexual misconduct not covered under Title IX — saw only modest improvements over prior years. This finding makes campuses’ disdain for the traditional due process protections that are the hallmark of any just system all too clear. There is simply no reason that protections like the presumption of innocence, the right to see the evidence against you, the right to face your accuser, or the right to a neutral decision-maker should be confined to students accused of sexual misconduct under Title IX.

Campuses went from the already confusing and unfair status quo of having two disciplinary systems with different rules — one for sexual misconduct, and one for all other misconduct — to having three such systems, simply adding another one for sexual misconduct governed under Title IX to comply with the new regulations. Instead of creating a single, well-run, and fair process, colleges and universities went out of their way to restrict student rights. That should disturb every American, especially the students whose educations are at risk and their tuition-paying parents.

Summary of Findings

In 2017, for the first time, FIRE rated the top 53 universities in the country (according to U.S. News & World Report) based on 10 fundamental elements of due process identified by FIRE. Our initial findings were troubling; the vast majority of institutions lacked most of the procedural safeguards that are customary in American justice system and that would be expected in colleges’ written policies. Since 2018, we have continued to assess the same institutions, but slightly adjusted our criteria in order to best capture the varied ways that universities adjudicate misconduct cases.

As noted above, the rated colleges showed a consistent unwillingness to apply the newly required regulatory protections for Title IX to contexts where they were not legally required. In practice, this meant that most rated colleges had three separate systems of disciplinary policies: one for sexual misconduct that takes place within the college’s educational program and is therefore covered by Title IX, one for sexual misconduct that the college believes it can punish but which did not take place in a context within its control (for example, between a student and a non-student while home on summer break), and one for all other non-academic offenses, such as theft, alcohol violations, property destruction, etc. FIRE therefore rated 156 policies among the 53 rated schools.

With the exception of Title IX processes, our 2021 findings are dire:

- Nearly two-thirds (62.2%) of America’s top 53 universities do not explicitly guarantee students that they will be presumed innocent until proven guilty. By contrast, more than 90% of rated college’s Title IX policies include a presumption of innocence.

- Three out of every four schools (75.4%) do not provide timely and adequate notice of the allegations to students accused of wrongdoing before expecting them to answer questions about the incident. By contrast, only ten schools (18.9%) have a Title IX policy that fails to provide such notice.

- Fewer than one out of every six schools (15%) guarantee a meaningful hearing, where each party may see and hear the evidence being presented to fact-finders by the opposing party, before a finding of responsibility. On the other hand, 34 schools (64%) have a Title IX policy that guarantees a meaningful hearing.

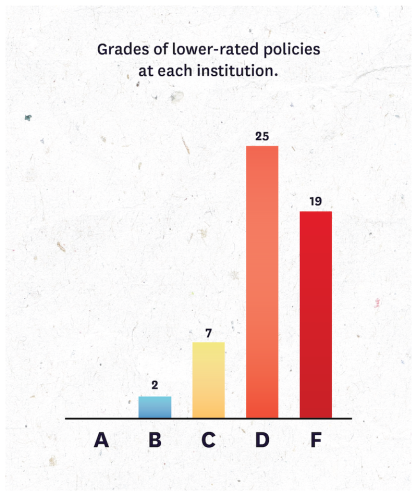

- A dismal 44 out of the 53 universities receive a grade of D or F from FIRE for at least one disciplinary policy, meaning that they fully provide no more than 4 of the 10 elements that FIRE considers critical to a fair procedure. This is nevertheless an improvement from the previous number of 49 out of 53 schools in the most recent prior report that earned a D or F.

- Most institutions maintain one set of standards for adjudicating charges of sexual misconduct and another set for adjudicating Title IX complaints. 72% of rated universities’ non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies receive a D or F for protecting the due process rights of students accused of sexual misconduct, as opposed to just 5 universities’ Title IX policies, less than 10%.

- Of the 156 policies rated at the 53 schools in this report, not a single policy receives an A grade, meaning that no policy provides more than 8 of the 10 elements that FIRE considers critical to a fair procedure.

- Compared to prior editions of this report, there were two significant changes overall in safeguards provided by the rated universities to students. First, thanks to the safeguards required by the new Title IX regulations, such policies were routinely the highest scoring policies at their institutions. Second, the mean score for non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies, while still very low, increased by more than two points, from 5.49, in last year’s report, to 7.64 out of a possible 20 points.

Six institutions received an F for both their non-Title IX sexual misconduct and other misconduct procedures: Georgetown University, Rice University, Boston University, Northwestern University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Notre Dame. Notre Dame stands out as the worst school overall, as it is the only institution that earned just one point for each of the two procedures.

In contrast, Cornell University’s disciplinary policies best incorporate the procedural safeguards in FIRE’s checklist, earning 15, 15, and 14 points, out of a possible 20 points, respectively, for its Title IX sexual misconduct, non-Title IX sexual misconduct, and other misconduct procedures. Georgia Institute of Technology also earned Bs across the board, earning 15, 15, and 13 points, for their Title IX sexual misconduct, non-Title IX sexual misconduct, and other misconduct procedures, respectively.

FIRE has publicly led the fight to restore due process on our nation’s campuses by highlighting abuses and bringing the attention of media, lawmakers, and the public to the problem. With this report, we hope to make abundantly clear to students, administrators, and policymakers across the country how badly reform is needed, and what kind of changes could benefit campus communities most.

Much needs to be done. The new Title IX regulations have led to some improvements in scores among non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies. But overall, the findings in this report — specifically, the fact that when forced to reexamine their policies, colleges chose to go out of their way to minimize the impact of new protections rather than design uniform, fair processes for all students — indicate that it is no longer credible to suggest that our nation’s universities will, on their own initiative, adopt policies likely to provide a fundamentally fair process to students.

Students and others who care about procedural rights should demand that colleges and universities take the necessary steps to protect those rights.

Methodology

For this report, FIRE analyzed disciplinary procedures at the 53 top-ranked institutions nationwide according to U.S. News & World Report’s National University Rankings for 2017, the year our first report was released. (The last four institutions that year were each ranked #50.)

Where institutions maintain different policies for academic and non-academic cases, we analyzed only the procedures for non-academic cases. Where institutions maintain different policies for cases in which suspension or expulsion may result and for cases limited to less severe sanctions, we analyzed only the procedures for cases involving potential suspension or expulsion. Where institutions maintain different policies for different colleges or graduate schools, we analyzed the policy for the undergraduate arts and sciences school at the main campus, unless otherwise specified. We did not consider faculty disciplinary procedures, which may differ significantly from those used for students.

Where, as in most cases, institutions maintain different policies for cases involving Title IX sexual misconduct complaints, alleged sexual misconduct not covered by Title IX, and other cases, we analyzed each set of policies. The vast majority of schools had maintained separate policies for sexual misconduct and other misconduct since the Office for Civil Rights issued its April 4, 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter, which imposed extensive new obligations on universities with regard to their handling of sexual misconduct claims. (This letter was rescinded on September 22, 2017, and, as noted above, the Department of Education has released new regulations to replace the rescinded instructions.) With the release of the new Title IX regulations, the vast majority of schools have adopted yet another set of additional policies in order to satisfy their legal obligations without extending many of their basic due process protections to other disciplinary proceedings.

Where institutions maintained their own policies but also purported to follow the policies of the broader state university system, both sets of policies were assessed together.

Some institutions may have revised their policies and procedures as FIRE was finalizing our research. Accordingly, this report might not reflect very recent policy changes.

In analyzing each set of disciplinary procedures, FIRE looked for 10 critically important procedural safeguards. For each element, institutions did not receive any points if the safeguard was absent, was too narrowly defined to substantially protect students, or was subject to the total discretion of an administrator; received one point if the policy provided some protection with respect to that element; and received two points if the safeguard was clearly and completely articulated.

FIRE recognizes that distilling the concept of due process down to 10 elements is necessarily reductive. In order to be truly “fair,” some proceedings may require elements we did not list or stricter adherence to those we did. In other proceedings, some of the safeguards we list may not prove to have an effect on the ultimate outcome. We welcome discussion about what we might include in future reviews or what was included that should not have been.

After each institutional policy set was awarded 0 to 20 points, it was graded as follows:

A = 17-20 points

B = 13-16 points

C = 9-12 points

D = 5-8 points

F = 0-4 points

Because each policy is written differently, points awarded to institutions are contingent upon wording, the overall structure of the proceedings described, and FIRE’s decision to resolve ambiguities against the institution where more clarity could reasonably be expected. Vaguely written provisions, or those that grant broad discretion to administrators, may easily be abused to deprive students of their right to a fair hearing, and therefore FIRE considers them inadequate to protect students and secure fundamentally fair proceedings.

Where institutions provide certain procedural safeguards only on appeal, and appeals are allowed only on certain grounds, the institutions do not earn points for those safeguards.

We awarded points for the following safeguards:

- A clearly stated presumption of innocence, including a statement that a person’s silence shall not be held against them.

In order to receive any points, the institution must explicitly include one of these elements in its policies. A statement that a respondent is allowed to decline to answer questions was not sufficient to earn full points, since this could simply mean that the student wouldn’t be punished for that choice as a separate matter from the pending case. Instead, the statement must specify that no negative inference, whatsoever, may be drawn from a student’s decision not to participate.

- Timely and adequate written notice of the allegations before any meeting with an investigator or administrator at which the student is expected to answer questions. Information provided should include the time and place of alleged policy violations, a specific statement of which policies were allegedly violated and by what actions, and a list of people allegedly involved in and affected by those actions.

For this safeguard to be meaningful, and thus earn one point, notice must include information about both the policy at issue and the underlying behavior, and it must explicitly be granted in advance of questioning. Where no time frame was specified, FIRE did not assume information would be given with sufficient time to prepare for interviews. An additional point was awarded for specificity of information and a guarantee of three or more days to prepare.

- Adequate time to prepare for a reasonably prompt disciplinary hearing. Preparation shall include access to all evidence to be used at a hearing as well as any other relevant evidence possessed by the institution.

For this safeguard to be meaningful, and thus to earn one point, an institution’s policy must explicitly state that evidence is shared in advance of the hearing. Providing parties access only to summaries of evidence was not sufficient to earn points. Any allowances for new evidence to be introduced after evidence is initially shared with the respondent must be narrowly written and should ensure that the respondent has adequate time to review the new evidence. Ideally, students would have at least seven days’ notice of the hearing date, at least five days with the evidence to prepare, and the ability to photocopy documents. Additionally, students should receive access to all evidence gathered, including not only evidence to be used against the respondent, but also exculpatory evidence. Full points were awarded to schools whose policies substantially encompass those elements.

- The right to impartial fact-finders, including the right to challenge fact-finders for conflicts of interest.

To receive one point, the institution must explicitly state that fact-finders must be free from conflicts of interest. Provisions instructing fact-finders to recuse themselves were not sufficient to earn a second point. General language in policy introductions broadly promising a fair or unbiased procedure was not sufficient to earn points. Articulating a process for students to challenge a fact-finder for conflicts of interest is necessary to earn two points.

- The right to a meaningful hearing process. This includes having the case adjudicated by a person — ideally, a panel — distinct from the person or people who conducted the investigation (i.e., the institution must not employ a “single-investigator” model) before a finding of responsibility.

Live hearings are best equipped to secure fair, reliable proceedings when they allow each party to directly observe all other parties (including an institutional prosecutor, complainant, and respondent) as they present evidence to the fact-finder, and to respond to that evidence in real time. Institutions that purport to employ a hearing but whose procedures left ambiguous whether a respondent would have the opportunities described above, or whose policies clearly impede these opportunities, were not awarded any points. For example, where the respondent is not able to see and hear as evidence is presented against them, or is allowed to respond only in a written statement, points were not awarded.

- The right to present all evidence directly to the fact-finders.

For this safeguard to be meaningful, and thus to earn points, students must be granted an opportunity to present all relevant evidence to the fact-finders — the person or people who decide whether or not the accused student committed the offense. Institutions did not receive any points if they limit the amount of relevant information a respondent can provide fact-finders directly, such as by imposing hard limits on how many words or minutes students may use for their arguments. Institutions also did not receive any points if they allowed someone other than the fact-finders and the respondent to determine what exculpatory evidence will be considered by the fact-finders (other than determining relevance). This includes policies that grant broad discretion to exclude the respondent’s choice of witnesses. Institutions received one point if a respondent may present all relevant evidence to fact-finders, whose determination must then receive final approval from an administrator or other individual.

- The ability to question witnesses, including the complainant, in real time, and respond to another party’s version of events.

Institutions were awarded a full two points for this safeguard if they explicitly allow respondents to cross-examine adverse witnesses in real time, either directly or through an advisor or chair who relays all relevant questions as written. Institutions received one point if respondents may cross-examine adverse witnesses through a third party, but the institution’s policy does not specify to what extent all relevant questions are relayed as written. Institutions did not receive any points where it is not clear that respondents have an opportunity to question adverse witnesses, where a third party has broad discretion to omit or reword questions, where questioning does not occur in real time, or where the respondent or fact-finder cannot see and hear the person testifying.

- The active participation of an advisor of choice, including an attorney (at the student’s sole discretion), during the investigation and at all proceedings, formal or informal.

For this safeguard to be meaningful, and thus to earn points, institutions must fully allow an attorney/advisor to speak on behalf of the respondent. Institutions were awarded one point if a non-attorney advisor may participate fully or if an attorney advisor may participate in a limited capacity, like cross-examining witnesses.

- The meaningful right of the accused to appeal a finding of responsibility.

Institutions were awarded full points if grounds for appeal included (1) new information or evidence that was previously unavailable, (2) procedural error, and (3) findings that were clearly not supported by the evidence. Institutions received one point if grounds for appeal included only two of these circumstances. To receive any points, the appellate decision-making body or individual must be different from the original fact-finders.

- A requirement that factual findings leading to expulsion be agreed upon by a unanimous panel or supported by clear and convincing evidence.

In order to earn points for requiring a unanimous fact-finding panel decision, panels must consist of three or more individuals.

Asterisks

Finally, FIRE has placed an asterisk by institutions whose policies grant an administrator or judicial body discretion to have a case adjudicated through a different, less protective procedure, or to not follow written procedures, without clear guidelines as to how such a decision may be made. We rated the more protective procedure and awarded an asterisk only where the disciplinary policy, as a whole, suggests that the procedure in question is the one ordinarily used. Where a student is very likely to be subjected to the less protective procedure, that was the one rated for this report.

Ratings

| Institution | Total Score of 20 | Letter Grade | Presumption of Innocence | Notice | Evidence Access | Conflicts | Hearing Process | Present Evidence | Cross-Examine | Advisor | Appeal | Clear and Convincing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston College* | 3/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Boston College Sexual Misconduct | 5/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Boston College Title IX* | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Boston University | 2/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Boston University Sexual Misconduct | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Boston University Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Brandeis University | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Brandeis University Sexual Misconduct | 5/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Brandeis University Title IX | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Brown University | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Brown University Sexual Misconduct | 5/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Brown University Title IX | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| California Institute of Technology | 1/20 | F | ||||||||||

| California Institute of Technology Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| California Institute of Technology Title IX | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Carnegie Mellon University | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Carnegie Mellon University Sexual Misconduct | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Carnegie Mellon University Title IX | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Case Western Reserve University | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Case Western Reserve University Sexual Misconduct | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Case Western Reserve University Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| College of William & Mary | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| College of William & Mary Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| College of William & Mary Title IX* | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Columbia University* | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Columbia University Sexual Misconduct | 7/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Columbia University Title IX | 16/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Cornell University | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Cornell University Sexual Misconduct | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Cornell University Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Dartmouth College | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Dartmouth College Sexual Misconduct | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Dartmouth College Title IX | 16/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Duke University | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Duke University Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Duke University Title IX | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Emory University | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Emory University Sexual Misconduct | 1/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Emory University Title IX | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Georgetown University | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Georgetown University Sexual Misconduct | 2/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Georgetown University Title IX | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Georgia Institute of Technology* | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Georgia Institute of Technology Sexual Misconduct | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Georgia Institute of Technology Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Harvard University | 3/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Harvard University Sexual Misconduct | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Harvard University Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Johns Hopkins University* | 5/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Johns Hopkins University Sexual Misconduct | 7/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Johns Hopkins University Title IX | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Lehigh University* | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Lehigh University Sexual Misconduct | 2/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Lehigh University Title IX | 2/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology* | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sexual Misconduct* | 2/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology Title IX | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| New York University* | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| New York University Sexual Misconduct | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| New York University Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Northeastern University* | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Northeastern University Sexual Misconduct* | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Northeastern University Title IX* | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Northwestern University | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Northwestern University Sexual Misconduct | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Northwestern University Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Pennsylvania State University | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Pennsylvania State University Sexual Misconduct | 5/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Pennsylvania State University Title IX | 10/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Pepperdine University | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Pepperdine University Sexual Misconduct* | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Pepperdine University Title IX | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Princeton University* | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Princeton University Sexual Misconduct | 10/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Princeton University Title IX | 16/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute | 3/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Sexual Misconduct | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Title IX | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Rice University* | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Rice University Sexual Misconduct | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Rice University Title IX | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Stanford University | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Stanford University Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Stanford University Title IX | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Tufts University | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Tufts University Sexual Misconduct | 3/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Tufts University Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Tulane University | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Tulane University Title IX | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of California, Berkeley | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of California, Berkeley Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of California, Berkeley Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of California, Davis | 10/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of California, Davis Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of California, Davis Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of California, Irvine | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of California, Irvine Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of California, Irvine Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of California, Los Angeles | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of California, Los Angeles Sexual Misconduct | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of California, Los Angeles Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of California, San Diego* | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of California, San Diego Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of California, San Diego Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of California, Santa Barbara | 10/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of California, Santa Barbara Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of California, Santa Barbara Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Chicago* | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of Chicago Sexual Misconduct | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| University of Chicago Title IX | 7/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of Florida | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of Florida Title IX | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Miami | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Miami Sexual Misconduct* | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Miami Title IX | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Michigan-Ann Arbor | 10/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Michigan-Ann Arbor Title IX | 11/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Notre Dame | 1/20 | F | ||||||||||

| University of Notre Dame Sexual Misconduct | 1/20 | F | ||||||||||

| University of Notre Dame Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Pennsylvania | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Pennsylvania Sexual Misconduct | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Pennsylvania Title IX | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Rochester* | 5/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of Rochester Sexual Misconduct | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of Rochester Title IX | 13/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Southern California | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Southern California Sexual Misconduct | 16/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Southern California Title IX | 16/20 | B | ||||||||||

| University of Virginia | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Virginia Sexual Misconduct | 10/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Virginia Title IX | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Wisconsin-Madison | 7/20 | D | ||||||||||

| University of Wisconsin-Madison Sexual Misconduct | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| University of Wisconsin-Madison Title IX | 9/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Vanderbilt University | 5/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Vanderbilt University Sexual Misconduct | 14/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Vanderbilt University Title IX | 16/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Villanova University | 4/20 | F | ||||||||||

| Villanova University Sexual Misconduct | 10/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Villanova University Title IX | 12/20 | C | ||||||||||

| Wake Forest University | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Wake Forest University Sexual Misconduct | 7/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Wake Forest University Title IX | 15/20 | B | ||||||||||

| Washington University in St. Louis | 5/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Washington University in St. Louis Sexual Misconduct | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Washington University in St. Louis Title IX | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Yale University | 6/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Yale University Sexual Misconduct | 8/20 | D | ||||||||||

| Yale University Title IX | 15/20 | B |

Trends

Written disciplinary policies and procedures varied greatly among the 53 schools FIRE rated for this report. There were, however, some notable trends.

Rating distributions, best institutions, and worst institutions

Of the 53 institutions and 156 policies rated for this report, none received an A grade.

Only two schools (Cornell University and Georgia Institute of Technology) received a B for each of their policies governing Title IX sexual misconduct, non-Title IX sexual misconduct, and other misconduct. Number ratings ranged from 1 to 16 out of 20. The median rating for each institution’s lowest-rated policy was a 6 out of 20, or a D.

Cornell University’s disciplinary policies best incorporate the procedural safeguards in FIRE’s checklist; it earned a B (14 points) for its procedures for other misconduct cases and a B (15 points) for both its non-Title IX sexual misconduct and Title IX sexual misconduct cases. Georgia Institute of Technology also received Bs across the board, with its other misconduct case procedures receiving 13 points and both its non-Title IX sexual misconduct and Title IX sexual misconduct case procedures receiving 15 points.

Stanford University earned a B (15 points) for its other misconduct cases and a high C (12 points) for its Title IX sexual misconduct cases, but earned only a D (8 points) for its non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy. The University of California, San Diego earned 14 points (a B grade) for its other misconduct policy and 13 points (also a B grade) for its Title IX policy, but earned a D grade (8 points) for its non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy. Vanderbilt University earned 14 points and 16 points, both B grades, for its non-Title IX sexual misconduct and Title IX sexual misconduct policies, respectively, but earned only 5 points, a low D grade, for its other misconduct policy.

Seven institutions received 4 points or fewer — an F grade — for at least two of their policies: Boston University, Georgetown University, Lehigh University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Northwestern University, Rice University, and the University of Notre Dame. Stunningly, Notre Dame received only 1 point for both its other misconduct and non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies.

Title IX versus non-Title IX sexual misconduct

When the Department of Education’s new regulations on Title IX took effect last August, institutions adopted new policies to comply. The impact of the regulations is clear in our grading: Title IX sexual misconduct policies were the highest-scoring type of policy at more than 85% of the institutions rated for this report, with only seven schools having any policy that earned more points than their Title IX policy. No institution’s non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy earned more points than their Title IX policy.

While schools could have simply incorporated the procedural safeguards into their existing sexual misconduct procedures, an overwhelming majority drafted an entirely new set of policies to address sexual misconduct covered by Title IX, while keeping in place existing policies for non-Title IX sexual misconduct. (This outcome was a foreseeable result of a provision in the regulation that noted that “inappropriate or illegal behavior may be addressed by a [school receiving federal funding] even if the conduct clearly does not meet the [Title IX sexual misconduct] standard or otherwise constitute sexual harassment under § 106.30, either under a recipient’s own code of conduct or under criminal laws in a recipient’s jurisdiction.” As a result, the majority of institutions developed two entirely separate definitions of sexual harassment with correspondingly distinct procedural protections. Such a process has invited administrators to decide which definition and procedures to apply to each case, a scenario that invites administrative abuse and puts due process rights at risk.)

Courts have since grappled with questions about the appropriateness of this approach. As the Northern District of New York wrote in Doe v. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, “the inevitable administrative headaches of a multi-procedure approach certainly qualifies as evidence of an irregular adjudicative process.” 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 191676, at *18 (N.D.N.Y. Oct. 16, 2020). The court went on to say that “[t]he absurd—yet necessary— result of an institution following [this multi-procedure approach] would be that school’s indefinite maintenance of an entire alternative procedure, perhaps behind a pane of glass labelled ‘Break in Case of Emergency,’ just in case a claim of sexual assault allegedly occurring before August 14, 2020 should arise.” As we have discussed, however, absurdity and impracticability have not prevented schools from doing everything they can to afford students as few protections as legally possible. In addition to causing administrative headaches, this multi-procedure approach has led to unbalanced due process protections across the different policies.

New Title IX policies provide valuable safeguards that are too often absent from non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies. Of the 53 surveyed institutions, Title IX policies at 45 institutions (84.9%) provide parties with the ability to question witnesses, in real time, during a Title IX hearing, while only nine institutions’ (18%) non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies provide the same safeguard.

Similarly, 45 schools (84.9%) maintain a Title IX policy that earned a point for allowing some active participation of an advisor during disciplinary proceedings, while only 10 schools (20%) use a non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy that earned a point for that same protection.

While many institutions went to great lengths to distinguish the policies, as mentioned above, there was nonetheless some “spillover” effect resulting in improved scores among non-Title IX sexual misconduct compared to previous years. The mean score for non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies rose to 7.64/20, a greater than two point increase over last year’s mean score of 5.49/20. While this is still significantly lower than the 12.62 mean score for Title IX sexual misconduct policies, that two point increase, while still within the D-grade range, marks the first time since our first report was released in 2017 that we have observed a significant change overall in safeguards provided by the rated universities to students.

This spillover effect manifests itself in a variety of ways. In many cases, institutions picked and chose provisions mandated by the new Title IX regulations to incorporate into their existing non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies. For example, many schools adopted better written notice provisions, as mandated by the new regulations, which mirrored the safeguards for which FIRE advocates, that were also included in the institution’s Title IX sexual misconduct policy.

A similar approach colleges and universities sometimes took was to adopt the same procedures for both Title IX sexual misconduct and non-Title IX sexual misconduct but provide specific carve-outs that allowed the school to avoid providing safeguards at critical junctures of non-Title IX sexual misconduct proceedings. For example, Dartmouth College’s proceedings are the same for much of the process, but include a specific subsection that states: “In a hearing that involves Prohibited Conduct that falls outside of Title IX jurisdiction, the parties shall not directly question one another.” Instead of permitting the parties to question each other through their advisor, as Dartmouth’s Title IX policy does, parties may suggest questions for the fact-finders to ask, which the fact-finders then have the discretion to ignore.

This means Dartmouth specifically drafted its non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy to ensure that the parties do not have the right to question witnesses. Despite this deliberate omission, by otherwise having its non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy mirror its Title IX policy, Dartmouth’s non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy’s score increased to 13 points, earning a B grade with a 4-point increase over its score in last year’s.

Yet even with the spillover effect, Title IX sexual misconduct policies score much higher marks across the board. 90% of surveyed institutions’ Title IX policies earned at least a C grade, with 60% earning a B. This is a stark contrast to this year’s non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies, as more than 70% of those policies earned either a D or F grade.

Sexual misconduct versus all other non-academic misconduct

All but three institutions rated for this report — Tulane University, the University of Florida, and the University of Michigan — maintain separate policies and procedures for the adjudication of cases alleging sexual misconduct.

Of the remaining 50 institutions, 23 institutions (46% of all rated institutions) maintain non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies that are less protective of students’ rights than other misconduct policies, 21 institutions (42%) maintain other misconduct policies that are less protective than sexual misconduct policies, and the two policy categories receive the same number of points at 6 institutions (12%). While this is an improvement over prior reports, there are still too many policies governing alleged non-Title IX sexual misconduct that provide fewer procedural safeguards. Sexual misconduct cases are often the cases in which procedural safeguards are most needed in order to ensure fundamental fairness and protect accused students against the life-changing effects of erroneous findings of responsibility. For example, cross-examination is a critically important tool in cases of alleged sexual assault, where cases are more likely to hinge on witness credibility because of the frequent lack of concrete evidence and the presence of few or no outside witnesses. As the Sixth Circuit wrote in Doe v. University of Cincinnati, “[W]e acknowledge that witness questioning may be particularly relevant to disciplinary cases involving claims of alleged sexual assault or harassment. Perpetrators often act in private, leaving the decision maker little choice but to weigh the alleged victim’s word against that of the accused.” 872 F.3d 393, 406 (6th Cir. 2017).

The mean score for other misconduct policies is 7.59 out of 20, while the mean score for non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies is 7.66. Only 16 institutions provide a meaningful hearing in non-Title IX sexual misconduct cases, while 29 institutions provide a meaningful hearing in other misconduct cases. The largest drop off in protections for students accused in non-Title IX sexual misconduct cases compared to other misconduct cases occurred at Lehigh University. Lehigh’s non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy earned only two points, nine fewer than its other misconduct policy. A similarly large gulf exists at Stanford University, as its non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy earned eight points — a D grade — while its other misconduct policy earned 15 points — a B grade.

On the flip side, some schools’ procedures for non-sexual misconduct cases earned fewer points than their non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies. The largest gap was at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where its other misconduct policy earned only three points — an F grade, and 11 points fewer than its non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy. Vanderbilt University saw a similarly large difference, with its other misconduct policy earning only five points — a low D grade — while the non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy earned 14 points and a B grade.

Notably, however, this is the first time the mean score for non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies was greater than that of other misconduct policies. This is also the first time that more schools than not maintained non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies that were more protective than other misconduct policies. While both policies’ mean scores earn a D grade, the more than two-point improvement of non-Title IX sexual misconduct scores is significant and, as discussed above, appears primarily to be a result of the implementation of recent Title IX regulations on campus.

Safeguard-specific trends

Alarmingly, 33 institutions (62.2% of rated schools) do not explicitly guarantee accused students the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. The presumption of innocence is perhaps the most fundamental right that can be granted to students accused of misconduct. Without it, other procedural safeguards still may not be enough to protect students from the risk of inaccurate findings of guilt. (For purposes of this section, unless otherwise specified, institutions are deemed to afford the safeguard being discussed if they guarantee that right in cases involving allegations of Title IX misconduct, sexual misconduct, and other non-academic misconduct.)

Of the procedural safeguards enumerated in FIRE’s checklist, the rarest among surveyed schools is the guarantee that a student’s expulsion be preceded either by a unanimous fact-finding panel decision or by a finding based on clear and convincing evidence: not a single school, of the 53 surveyed, provided this guarantee. Courts have questioned whether, in the high-stakes setting of a sexual misconduct adjudication, preponderance of the evidence is a sufficiently high standard to effect due process. See Doe v. University of Mississippi, 361 F. Supp. 3d 597, 613 (S.D. Miss. Jan. 16, 2019); Doe v. DiStefano, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 76268, at *6 (D. Colo. May 7, 2018).

Nearly as rare is the right to active assistance from an advisor of the student’s choice. Only two schools (3.7%) allow attorneys to participate in all non-academic cases without significant limitations: the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Cornell University. Instead, most rated institutions simply allow students to have an advisor of their choice accompany them to meetings and hearings, so long as the advisor doesn’t actively participate.

The right to conduct meaningful cross-examination and receive advance written notice of the allegations against a student — including the policy at issue and underlying behavior — were also exceedingly rare. For cross-examination, 47 out of 53 schools (88.6%) did not receive any points, and for advance written notice, 40 schools (75.4%) did not receive any points, meaning that they do not guarantee students these safeguards in at least some non-academic cases.

As a number of courts have recognized, the ability to cross-examine witnesses in real time is particularly crucial in campus sexual assault cases; these cases often lack witnesses and physical evidence and therefore may rely heavily on the relative credibility of the accuser and the accused. In September 2018, in a case succeeding Doe v. University of Cincinnati, the Sixth Circuit held in Doe v. Baum that cross-examination is an essential element of due process in campus judicial proceedings turning on credibility. The court wrote that “if a public university has to choose between competing narratives to resolve a case, the university must give the accused student or his agent an opportunity to cross-examine the accuser and adverse witnesses in the presence of a neutral fact-finder.” 903 F.3d 575, 578 (6th Cir. 2018). In August 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit issued a decision in Haidak v. University of Massachusetts Amherst, quoting FIRE’s amicus curiae brief to hold that “due process in the university disciplinary setting requires ‘some opportunity for real-time cross-examination, even if only through a hearing panel.’” And in May 2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held in Doe v. University of the Sciences that “contractual promises of ‘fair’ and ‘equitable’ treatment to those accused of sexual misconduct require at least a real, live, and adversarial hearing and the opportunity for the accused student or his or her representative to cross-examine witnesses — including his or her accusers.” 961 F.3d 203 (3d Cir. 2020).

Yet 38 institutions (76%) do not provide students a meaningful opportunity to cross-examine witnesses in cases of non-Title IX sexual misconduct. Only four institutions (7.5%) provide an opportunity for cross-examination in all non-academic cases and clear guidelines that ensure all relevant questions are relayed to the party being questioned.

The right to sufficient time, with access to all relevant evidence, unless it is subject to a legal privilege, to prepare for a hearing is not guaranteed at 37 schools (70%), and it is guaranteed as robustly as FIRE believes is appropriate at only one institution (1.9%), New York University. The importance of guaranteeing access to all relevant evidence, including exculpatory evidence, is highlighted by cases such as one accused student’s lawsuit against the University of Mississippi, in which the plaintiff alleged that the university’s Title IX coordinator deliberately refused to consider certain exculpatory evidence. Doe v. University of Mississippi, 361 F. Supp. 3d 597 (S.D. Miss. 2019). And in 2018, a judge overturned a guilty finding by the University of California, Santa Barbara, holding that it denied an accused student access to critical evidence in his case. The judge ruled that “without access to the [medical] report, John [Doe, the accused student] did not have a fair opportunity to cross-examine the detective and challenge the medical finding in the report. The accused must be permitted to see the evidence against him. Need we say more?” Doe v. Regents of the University of California, 28 Cal. App. 5th 44, 57 (Cal. Ct. App. Oct. 9, 2018).

The right to a meaningful hearing in front of a fact-finding panel is not guaranteed at 42 institutions (79.2%). Of these, many refer to their core proceedings as a “hearing,” but fail to provide the critically important elements described in the Methodology section above, such as an opportunity for each party to see and hear the evidence being presented to fact-finders by the opposing party.

Courts have taken notice of the problematic nature of the “single-investigator model” that replaced many disciplinary hearings in recent years, particularly in sexual misconduct cases. While the Title IX regulations do not permit such a process, some non-Title IX sexual misconduct policies retain it. Harvard University’s non-Title IX sexual misconduct policy provides a good example of this model: “At the conclusion of the investigation, the Investigation Team will make findings of fact, applying a preponderance of the evidence standard, and determine based on those findings of fact whether there was a violation of the Policy.” This policy is noteworthy because it represents a slight improvement over a prior policy that utilized only a single investigator, instead of the new “Investigation Team.” Yet Harvard continues to have the same individuals investigate and then adjudicate a student’s case, leaving many of the same fundamental due process issues in place.

In upholding an accused student’s challenge to a similar policy at Brandeis University, a federal judge in Massachusetts wrote: “The dangers of combining in a single individual the power to investigate, prosecute, and convict, with little effective power of review, are obvious. No matter how well-intentioned, such a person may have preconceptions and biases, may make mistakes, and may reach premature conclusions.” Doe v. Brandeis University, 177 F. Supp. 3d 561, 606 (D. Mass. 2016).

The right to challenge fact-finders for bias or partiality is guaranteed at only 20 institutions (37.7%). An additional 15 institutions (28.3%) specify that fact-finders should be impartial, but do not specifically provide a mechanism for students to challenge their participation in a case. Yet the impartiality of fact-finders is something that courts take very seriously. Several court decisions favorable to accused students, for example, have involved allegations that the university used biased materials to train its Title IX hearing panels (The new Title IX regulations require such materials be made public.) In Doe v. University of Mississippi, the court held: “This is a he-said/she-said case, yet there seems to have been an assumption under [the] training materials that an assault occurred. As a result, there is a question whether the panel was trained to ignore some of the alleged deficiencies in the investigation and official report the panel considered.” 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 123181, at *28-29 (S.D. Miss. July 24, 2018). Similarly, in Doe v. Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania, the court held that “the Complaint’s allegations regarding the training materials and possible pro-complainant bias on the part of University officials set forth significant circumstances suggesting inherent and impermissible gender bias to support a plausible claim” that the university discriminated against the accused student on the basis of sex. 270 F. Supp. 3d 799, 824 (E.D. Pa. 2017).

Students have the right to present all relevant evidence directly to fact-finders at only 10 institutions (18.8%). Students at 40 institutions (75.5%) are limited in what relevant evidence they may present to fact-finders and sometimes cannot present evidence directly to fact-finders at all.

Among the most commonly granted procedural safeguards is the right to appeal, particularly based on new information or procedural errors. Of the 53 surveyed institutions, 5 schools (9.4%) allow for appeals based on all three grounds to which FIRE looks: new information, procedural errors, or if the finding is not consistent with the weight of evidence on the record. Additionally, 44 schools (83%) allow for appeals based on two of the three grounds enumerated in FIRE’s checklist. Only four institutions failed to provide the right to appeal on more than one of these grounds.

FIRE believes these safeguards are essential in order to ensure fair proceedings for all students. While some safeguards, such as the presumption of innocence, specifically protect accused students against erroneous findings of responsibility, most of these safeguards are tailored to allow all parties and fact-finders to receive all relevant information in an organized fashion so that the results are as accurate as possible. This goal serves all students, as well as the rest of the campus community, as the impact of these proceedings is often felt throughout the institution. Ensuring that the proceedings are conducted in an equitable and reliable manner is of the utmost importance. Yet, at most surveyed institutions, disciplinary policies and procedures do not appear designed to reach that goal.

Educational versus adversarial processes

Many institutions emphasize in their written policies that the disciplinary process is meant to be “educational”, not “adversarial.” But with students facing sanctions as serious as expulsion, with alleged facts in dispute, and with some underlying offenses also constituting criminal behavior, many of the cases institutions adjudicate are necessarily adversarial. To characterize the process as merely “educational” is to ignore the very serious impact that the outcomes can have on students’ lives. Indeed, in response to a University of Notre Dame administrator’s testimony that the university’s sexual misconduct adjudication process was an “educational” process (and thus that important procedural safeguards were unnecessary), a federal judge in Indiana put it bluntly: “This testimony is not credible. Being thrown out of school, not being permitted to graduate and forfeiting a semester’s worth of tuition is ‘punishment’ in any reasonable sense of that term.” Doe v. University of Notre Dame, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 69645, at *34-35 (N.D. Ind. May 8, 2017).

Yet some institutions explicitly reject important safeguards in the name of preserving an “educational” process. The University of Wisconsin-Madison, for example, does not maintain a policy that states that an accused student’s silence shall not be held against them. In fact, Wisconsin’s policy goes in the opposite direction: “In accordance with the educational purposes of the hearing, the respondent is expected to respond on the respondent’s own behalf to questions asked of the respondent during the hearing.” In 2020, a federal judge rejected the University of Colorado’s argument that it was necessary to limit procedural safeguards to avoid “convert[ing] its classrooms to courtrooms,” saying “this interest truly pales in comparison to the risk of error which may result in the wrongful expulsion of a student.” Messeri v. DiStefano, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 150942, at *12 (D. Colo. Aug. 20, 2020).

Moreover, unavoidably “adversarial” exchanges may be necessary in order for fact-finders to determine which of two competing factual narratives is more accurate. As the court explained in Baum, “adversarial questioning” is of critical importance “because it does more than uncover inconsistencies—it ‘takes aim at credibility like no other procedural device.’” Finally, the presumption that all students accused of misconduct have a lesson to learn from the process – thus rendering it “educational” – makes sense only if one begins with the presumption that every accused student is guilty of at least some sort of wrongdoing. If not, the argument that hearings are “educational” amounts to the unconscionable argument that being forced to defend one’s self from erroneous or unjust accusations may be a legitimate part of an institution’s educational experience. In order to maintain a presumption of innocence in practice, therefore, institutions must acknowledge the inherently adversarial nature of any case where the accused student does not admit responsibility.

A few institutions do, however, understand what the aim of disciplinary procedures should be. The University of Rochester, for example, states: “The purpose of a formal conduct hearing is to determine the truth about a respondent’s alleged misconduct.” The safeguards sought for this report further exactly this purpose.

Discretion to omit procedural safeguards

Written provisions designed to help fact-finders do their job well and to protect against inaccurate findings should be guaranteed fully for all students subjected to the disciplinary process. These safeguards may not help students if administrators are granted broad discretion to omit them, or if there are exceptions to those safeguards that threaten to swallow the rule. Unfortunately, this is the case at many universities.

As noted above, the institutions marked by an asterisk are those at which an administrator or judicial body decides between two or more potential channels through which a case can be resolved. Provisions allowing for alternative procedures often do not describe the alternative procedures or explain when the adjudicating entity would choose one procedure over another. Each of these shortcomings leaves students unsure of which safeguards are fully guaranteed at their institutions, and makes it all too easy for institutions not to provide respondents with a fair hearing.

Many of the policies reviewed grant discretion to administrators to omit procedural safeguards, without adequate guidelines to limit that discretion. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s other misconduct policy, for example, provides broad discretion for the chair to determine “whether certain witnesses should appear” and “whether any particular question, statement, or information will be allowed during a hearing,” with little limitation on that discretion. At Boston University, its other misconduct policy states that the chair “may permit” questioning by the respondent — but such questioning is not guaranteed. At Carnegie Mellon University, its other misconduct policy explains that respondents will be provided a packet of information “which may include” relevant evidence that will be used against them — but this critical safeguard is not guaranteed.

Sometimes this discretion is framed as the discretion to provide certain safeguards — which, in practice, is no better than the discretion to withhold them, as the administrative discretion still facilitates unequal application of policies among students facing similar charges. For example, at the University of Pennsylvania, advisors may be allowed to question witnesses at the hearing officer’s discretion.

Limiting witnesses, questions, evidence, or access to counsel to that which an administrator deems “appropriate” similarly leaves administrators free to follow their whims without any guidelines to ensure equal and equitable application of policies. In Princeton University’s non-Title IX sexual misconduct procedures, for example, questions will be allowed if relevant — but the chair has “the sole discretion to determine what questions are relevant.” In Pepperdine University’s Title IX misconduct policies, a respondent is permitted to confer with their advisor during their hearing — but if they do so “repeatedly,” they may be informed that “such conduct will be considered when weighing the party’s credibility.”

In the University of Rochester’s non-Title IX sexual misconduct procedures, a single administrator possesses “discretionary authority to determine whether particular questions, evidence or information will be accepted or considered, including whether a particular witness will or will not be called and, if called, the topic(s) that the witness or the parties will be permitted to address.” This level of absolute discretion undermines fundamental procedural safeguards and is ripe for abuse. Without stronger, explicit limits on this discretion, policies like this one essentially ensure that no two proceedings will be treated the same, undermining fundamental fairness.

As discussed above, many schools justify this broad discretion by harkening back to their educational purpose. Princeton University, for example, asserts in its disciplinary policy that “rigid codification and relentless administration of rules and regulations are not appropriate to an academic community … .” This is surely not true, however, with regard to disciplinary processes intended to deter and determine responsibility for serious, sometimes criminal, misconduct. Likewise, scattered throughout other policies among these 53 schools are words like “generally,” “normally,” “ordinarily,” “typically,” and “usually,” each providing opportunities for administrators to ignore written procedures in favor of ad hoc decision-making that may be arbitrary at best, or discriminatory at worst.

Numerous, inconsistent, unclear, and inaccessible policies

Students’ ability to obtain a fair hearing is hindered not just by policies that lack procedural safeguards, but also by confusing, poorly drafted, or difficult-to-access policies. In assessing disciplinary procedures for this report, the following problems became readily apparent and require attention.

Multiple policies

As noted, nearly all institutions rated for this report maintain not one policy, or even two, but three policies for non-academic misconduct alone that overlap and sometimes conflict with each other. Multiple policies inevitably confuse students and administrators, and make it harder for fair disciplinary proceedings to take place. They also increase the potential for procedural inconsistencies among similar cases.

As has been the case since the first edition of this report, the six rated campuses of the University of California system follow system-wide policies, but also maintain their own individual, overlapping disciplinary policies. As a result, students may have to sift through several different policies even for the same type of offense before they can get a full understanding of their rights, and students attending different institutions within the UC system are left with drastically different procedural rights. Students in the UC system would be better served if the system consolidated its overlapping policies and ensured that safeguards which are presently only granted in some cases at some campuses are instead guaranteed at all campuses in all non-academic cases where suspension or expulsion are potential sanctions.

Poorly drafted policies

Policies at several institutions, including the California Institute of Technology, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and the University of California, Irvine, lack important details about what exactly happens during hearings and other proceedings. Because of these omissions, it is difficult to tell whether students are guaranteed an opportunity to question witnesses or present evidence directly to fact-finders. Like other ambiguous or vague provisions, these insufficiently detailed policies create an opportunity for administrators to treat cases differently based on a desire for a certain outcome or prejudice against a certain party or type of allegation.

It is also possible that students at some institutions are afforded greater procedural safeguards in practice than those they are explicitly guaranteed in writing. Administrators who are aware of such discrepancies must aim to codify into written policies all those procedural safeguards they provide in practice. This way, students can be confident that all respondents receive the same procedural protections, and that administrators’ successors will enforce a given policy in an equally protective way.

The University of California system, for example, states that parties “will be able to see and hear all questioning and testimony at the hearing, if they choose to” — but this statement fails to say whether all parties will be able to see and hear each other at all other points of the hearing. Pennsylvania State University’s Title IX policy guarantees that written notice will include information about the alleged behavior that forms the basis of the complaint, but fails to guarantee that the notice will specify what policies are allegedly violated by that behavior. Specifying what policies are implicated is particularly important as many schools now have multiple systems to investigate sexual misconduct. It is vital that institutions do everything they can to limit potential confusion for students.

Moreover, where institutions’ ratings have suffered because of imprecise language or administrators’ reliance on the mere implication of a safeguard, those schools may easily improve their ratings by simply revising the language of their policies to be clear and explicit. Tulane University, for example, states that, before an investigative report is finalized, “necessary individuals and/or organizations will be given the opportunity to review a draft of the investigation report,” without stating who these necessary individuals may be. Perhaps Tulane typically considers respondents a necessary individual and shares the investigative report with them. However, by not specifying as much in its written policies, Tulane leaves open the possibility that respondents will be denied access to information critical to their proceeding. FIRE cannot give institutions the benefit of the doubt on such critical questions for the purpose of this report.

Some institutions may better protect students by simply eliminating unnecessary and problematic alternatives to appropriate standard hearing formats, or by eliminating unnecessary provisions granting administrators discretion in certain areas. The University of Florida allows parties to participate in the hearing process “via audio or live-video from another location.” As a result of the audio options, not all respondents will necessarily be able to see and hear the complainant as they testify. The policy states that this is intended to provide complainants with the ability to avoid direct contact with the accused student, but that objective could be met by the live-video option, which still allows all parties to see and hear each other, and which is more readily available now than ever before.

Still other institutions initially appear to grant students procedural rights but then maintain provisions that serve to negate those rights. Yale University allows students to request witnesses to appear at their hearing, but then states: “The invitation of any witness will be made at the discretion of the Coordinating Group.” Such unfettered discretion means students are not truly guaranteed the right to present and question witnesses.

Inaccessible policies

Finally, while a majority of institutions post each set of policies governing disciplinary procedures in one searchable PDF or on one searchable webpage, some institutions split policies into many pages or sub-pages that cannot be searched, printed, or conveniently viewed all at once.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for example, keeps its policies and procedures in several different locations on its website, with a variety of drop-down menus that require a user to take a piecemeal approach to reading the procedures. This makes it impossible for students to view the policies all at once, in a single document. Pennsylvania State University also keeps its policies on a page with different sections, of which a user may only view a single section at a time, as opening one section automatically collapses the other section.

Fortunately, a previous trend of policies that cannot be copied and pasted or searched at all may be coming to an end. Each year, a number of institutions whose policies previously were in image form or that copied and pasted incorrectly become available in normal text.

Incorrect or dead links, however, continue to plague university websites and can cause confusion for students and administrators. For a few examples, Northwestern University, Northeastern University, and California Institute of Technology each had broken, incorrect, or outdated links on their student conduct websites or in their conduct documents. Broken or incomplete pages and links can leave students wondering whether they are missing important information about their rights and the disciplinary process.

Other institutions include all relevant disciplinary provisions in a single document but include incorrect links that can cause confusion for students and administrators. For example, Lehigh University’s website continues to link to an outdated handbook that was last updated in 2015. While a more recently updated version is linked elsewhere, it is important for all institutions to take care to remove from their websites or place prominent notices on all policies that are no longer in effect, including those that are not linked but that have been indexed by search engines.

In order to best protect students’ right to fundamentally fair disciplinary proceedings, institutions should strive to unify all applicable disciplinary policies and procedures into one clear and internally consistent document. This document should be searchable and easily located on the college’s website. This makes it easier for members of the campus community to find, learn, enforce, and abide by school policies, and it allows administrators to update the website with new policies without a high risk of broken links and old policies remaining visible.

Conclusion: Institutions Nationwide Must Revise Policies to Protect Student Rights

Thanks to the new regulations, students in Title IX hearings now have much improved due process rights. But students dealing with any other campus charges still face wildly unjust kangaroo courts. While most of the deficiencies discussed above may be readily fixed through policy revisions, FIRE’s research reveals that institutions are refusing to implement fair disciplinary processes for all students. As the leader in the fight for student rights nationwide, FIRE stands ready to help institutions, lawmakers, and other stakeholders work to revise these disciplinary policies and procedures to better protect due process rights and fundamental fairness.

Administrators or students who would like to work with FIRE in support of fair policies are encouraged to contact us at dueprocess@thefire.org.