Table of Contents

FIRE Report: MIT’s Institutional Health

About Us

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to defending and sustaining the individual rights of all Americans to free speech and free thought. These rights include freedom of speech, freedom of association, due process, legal equality, religious liberty, and sanctity of conscience — the most essential qualities of liberty. FIRE also recognizes that colleges and universities play a vital role in preserving free thought within a free society. To this end, we place a special emphasis on defending these rights of students and faculty members on our nation’s campuses.

For more information, visit thefire.org or @thefireorg on Twitter.

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes to Komi Frey, Sean Stevens, Andrea Lan, and Adam Goldstein for conceptualizing and conducting this research, and for authoring this report.

Suggested citation: Frey, K., Stevens, S.T., Lan, A., & Goldstein, A.,(2023). FIRE Report: MIT’s Institutional Health. Available online at: https://www.thefire.org/research-learn/fire-report-mitsinstitutional-health

Introduction

MIT's innovation is unmatched, and to keep it that way, it must defend academic freedom.

In 2022, MIT ranked second in U.S. News and World Report’s Best National University Rankings. What’s more, for the 11th year in a row, MIT was named the top university in the world by the QS World University Rankings. And for good reason. MIT has 3,543 patents active in the U.S., 730 invention disclosures, and affiliations with 100 Nobel Prize laureates. Just last year, MIT’s eminent Lincoln Laboratory developed six R&D award-winning technologies, including a hurricane-tracking satellite, a quiet propeller design for small commercial drones, a collision-prevention system for drones flying in national airspace, a cybersecurity tool, and two radio frequency-reducing systems.

What makes MIT’s innovation possible? Academic freedom. The unparalleled success of MIT is a testament to what can happen when researchers are allowed to freely explore intellectually uncharted — or even forbidden — territory.

Yet there are signs of weakness in MIT’s commitment to academic freedom. The decision to rescind University of Chicago geophysicist Dorian Abbot’s invitation to deliver the annual John Carlson Lecture, hosted by MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, has raised concerns about the institutional climate that allowed such censorship to occur. Community members have formed the MIT Free Speech Alliance, which has received a $500,000 grant from the Stanton Foundation to advance its mission of free speech and expression, viewpoint diversity, and academic freedom at MIT. They are advocating for the adoption of stronger academic freedom protections, such as the Chicago Statement. (See our “Fast Facts” overview for more.)

While MIT is a private university, its mission and objectives describe an institution where students and faculty engage in unfettered intellectual exploration. Yet according to the largest survey ever conducted on students’ free speech attitudes, MIT students show worrying signs of intolerance, and MIT appears to be failing to teach them the value of academic freedom. FIRE’s survey of MIT faculty reveals that faculty are mostly supportive of academic freedom and would like the administration to do its part to improve the climate for free expression at the institution. The “Letter by 77 Faculty Re: Professor Abbot’s Lecture Cancellation” suggests that faculty members are aware and concerned. Finally, our data on the dissolution of tenure at MIT portends a speech-chilling future.

In this report, we: (a) reflect on the report by MIT’s ad hoc working group on free expression and how it pertains to the cancellation of Dorian Abbot’s Carlson Lecture; (b) share data on MIT faculty members’ attitudes about the cancellation of Abbot’s lecture and academic freedom issues broadly; (c) compare MIT student and faculty attitudes toward free expression to each other and to national student and faculty samples; (d) examine the threat to academic freedom posed by the erosion of tenure at MIT; and (e) provide recommendations for improving MIT’s existing policies to ensure that MIT faculty and students are afforded maximum latitude to inquire.

MIT's Working Group on Free Expression

Report struggles to take a clear position on academic freedom

First, a word regarding MIT’s recent report on free expression. Although we admire the president, provost, and chancellor’s directive to create the Ad Hoc Working Group on Free Expression, the group was unable or unwilling to articulate its position clearly. Specifically, the group fails to specify whether it will prioritize a commitment to diversity or to academic freedom. At some points in the report, the group suggests that academic freedom will prevail, but at other points it suggests that it’s more “complicated.” The group explains, “Recent campus speech controversies have given rise to the appearance that these two values [free expression and anti-racism] are in conflict at some foundational level. The historical reality is more complicated” (p. 9).

The complicating factor, the report states, is that black college students do not feel protected by the First Amendment, and thus favor campus environments that prohibit offensive speech. This observation leads the working group to assert that “proponents of free expression have failed to make the case for open and uninhibited debate in terms that are informed by our nation’s history of racial subordination.” (pp. 9-10).

Comments from an MIT Faculty and Student

We attended a meeting hosted by the MIT Free Speech Alliance, in which professor Ed Schiappa — who helped write the report — admitted that vague, even conflicting, messages reflect disagreement among group members regarding their positions. “One of the reasons it took us until late June is that we really wanted 100% buy-in on the entire report. And, so sometimes you do have things in there that are a function of keeping certain people happy so that they let you be happy,” Schiappa explained. When asked to clarify specific caveats and hedges in Recommendation 5 and 6 on page 21 of the report, Schiappa replied, "I wrote the original version of recommendation 6. The original version is pretty much what you see in the bolded part. What comes after the bolded part, I did not write." If the group cannot even stand up to its own members, how can it be expected to stand up to people on and off campus who demand the subordination of academic freedom?

As one MIT undergraduate student put it, “Students were upset about the geology dude coming to give a talk but it was perfectly acceptable by all tokens.” If only the administration, and the working group for that matter, could have said as much.

“One of the reasons it took us until late June is that we really wanted 100% buy-in on the entire report. And, so sometimes you do have things in there that are a function of keeping certain people happy so that they let you be happy."

— Ed Schippa, contributing author of the report and member of MIT Free Speech Alliance

The ad hoc group did not even offer their position on the cancellation of Dorian Abbot’s Carlson Lecture. Instead, it presented two opposing positions: one held by MIT undergraduates, and the other by MIT alumni. According to the Undergraduate Association, students generally supported the department’s decision to cancel the Carlson Lecture, because they believed Abbots’ diversity, equity, and inclusion views would distract from the outreach objectives of the event. Moreover, students did not see the cancellation as an infringement on freedom of expression because Abbot was provided an alternative setting at MIT in which to deliver his lecture. Many MIT alumni, by contrast, were embarrassed and disappointed by MIT’s actions, felt a loss of pride in being associated with MIT, and would no longer donate due to the loss of trust.

Why didn’t the working group on free expression state its position on Abbot’s free expression? It came closest at a later point in the report, when it stated, “Rescinding an invitation to deliver protected speech, as defined and explained in this report, conflicts with freedom of expression.” Schiappa confessed that the group was explicitly instructed it was not their charge to revisit the cancellation of the Carlson Lecture. Presumably, the incident was already sufficiently addressed. Case closed.

Students did not see the cancellation as an infringement on freedom of expression because Abbot was provided an alternative setting at MIT in which to deliver his lecture. Many MIT alumni, by contrast, were embarrassed and disappointed by MIT’s actions, felt a loss of pride in being associated with MIT, and would no longer donate due to the loss of trust.

Although the cancellation has already received extensive coverage, much of that coverage discussed widespread discontent with the administration’s public statements, which attempted to minimize the erosive effects of cancellation on academic freedom. Failure to acknowledge the administration’s mistake, and to state unequivocally that it will not happen again, can only raise doubts about what MIT will do if and when it is faced with another conundrum.

Dorian Abbot's Lecture Cancellation and Academic Freedom

From speaking with people within the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, it is our understanding that Dorian Abbot was disinvited because the purpose of the Carlson Lecture is to promote MIT courses to high school students around Boston, many of whom are disadvantaged and black. Therefore, it was deemed inappropriate to invite someone who opposes affirmative action and has argued that DEI initiatives at American universities have a chilling effect on campus speech and violate the ethical and legal principle of equal treatment.

There was reason for MIT’s EAPS faculty to be concerned about the psychological impact of having Dorian Abbot deliver the Carlson Lecture. After all, underrepresented students could read Abbot’s op-ed and come to believe that if they benefit from affirmative action, they are inferior and less deserving of being selected to join prestigious institutions like MIT. Such beliefs may diminish their motivation to pursue science.

What Does the Research Say?

There is some research that supports this hypothetical chain of events. Recipients of affirmative action can be stigmatized as incompetent by both others and themselves.[1] Specifically, affirmative action, and the associated possibility that demographics play a role in selection, may cause recipients to doubt their competence.[2] Furthermore, perceived incompetence contributes to poor performance outcomes.[3] This may occur because threats to a positive self-image trigger negative emotions such as stress and anxiety,[4] which hinder performance.[5]

With this in mind, it was reasonable for MIT to consider how disadvantaged and under-represented minority high school students, upon reading Abbot’s op-ed critical of DEI, may have been discouraged from attending and engaging with Abbot, even on the unrelated topic of geophysics. Rather than cancel Abbot’s lecture, however, the EAPS faculty could have spoken just prior to the lecture to explain why Abbot’s discipline-specific expertise made him an excellent candidate to speak to, and educate, the students. They could also have emphasized that Abbot’s views on DEI are unrelated to the invited talk and do not represent the views of the EAPS faculty, or MIT broadly. This would have allowed Abbot to deliver his Carlson Lecture as planned, while also allowing the concerned faculty to reassure any students who may have felt marginalized by Abbot’s op-ed.

Instead, the EAPs faculty and MIT administration sent the message that people with certain views cannot speak to certain people, even if those views are unrelated to the topic of the speech at hand.

MIT Faculty Survey Results

This past summer, we sent a survey to all faculty members, postdoctoral researchers, and graduate students listed on MIT’s website (N = 1,475). The purpose of this survey was to gauge their views on academic freedom in general and on the Dorian Abbot controversy in particular. A total of 195 faculty completed the survey, for a response rate of 13%. While this response rate may seem low, it is slightly higher than that of other recent studies of university faculty, on which response rates have fallen between 2% and 7%.[6] Furthermore, evaluations of surveys with response rates ranging from 5%-54% indicate that studies with a lower response rate are only marginally less accurate than those with higher response rates.[7]

First and foremost, the majority of MIT faculty members surveyed (52%) think that the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences was wrong to cancel Abbot’s John Carlson Lecture, compared to the 16% who think the department was right to do so.[8] Next, when asked specifically about mandatory diversity statements in faculty hiring, nearly half of MIT faculty (46%) say that such statements are “an ideological litmus test that violates academic freedom.” However, a little over a third (37%) consider them “a justifiable requirement for a job at a university,” suggesting that MIT faculty have mixed attitudes toward requiring DEI statements in hiring.

Yet, when asked about DEI initiatives broadly, MIT faculty favor free expression and academic freedom. For instance, when asked how the administration should respond to professors refusing to take mandatory diversity training, 60% believe “no action of any kind should be taken,” or “no formal disincentives should be issued.” In contrast, one-fifth (20%) of MIT faculty believe the professors should face professional sanctions, including lost work opportunities (12%), suspension until they comply (7%), or termination (1%). Finally, when given a hypothetical scenario asking how the administration should respond to student demands that an MIT professor be fired for authoring an op-ed in a national news outlet that criticizes university efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion on campus, almost two-thirds (63%) of MIT faculty say that the administration should defend the professor’s free speech rights, 18% say the administration should condemn the speech but not punish the professor, and just 6% say the professor should be investigated. Not a single MIT faculty member thinks that this hypothetical colleague surveyed should be removed from the classroom, suspended, or terminated.

In sum, these findings show that most of MIT’s faculty opposed the disinvitation of Dorian Abbot, believe that academic freedom should protect extramural expression critical of DEI, oppose sanctions for refusal to comply with mandatory diversity training, and are likely somewhat skeptical of requiring DEI statements in the faculty hiring process.

These findings stand in stark contrast to the position of the MIT working group on free expression: “A professor who criticizes DEI programs and is then dismissed from her role at the Institute would be a clear example of illegitimate punishment that is hostile to free expression. A professor who is denied a promotion (such as leading a department or assuming another leadership role) is a more complicated matter” (p. 18). As mentioned above, not one MIT faculty member surveyed believed that a professor should face anything more than an investigation for taking such a position, and the majority said that administration should defend the faculty member’s freedom of speech.

Moreover, the group asserts that “if the professor in question announces that she will refuse to apply MIT’s DEI policies, which seems no different from stating that she will refuse to apply any other MIT policy, we may reasonably question whether such a person should lead a DLC [Department, Lab, or Center]” (p. 18). As mentioned above, only one-fifth (20%) of MIT faculty we surveyed believe professors should face professional sanctions if they fail to comply with mandatory DEI training. Nevertheless, the group believes that “in such cases, the MIT president may very reasonably conclude that she would not make a good candidate for a deanship. The Institute has no legal or other obligation to protect MIT community members from the political consequences of their own speech. Free speech is not the same thing as speech that is free of consequences.”

One of the primary arguments against DEI initiatives is that they can create a chilling effect. When presented with a definition of self-censorship and then asked if they were more or less likely to self-censor on campus today compared to before the start of 2020, 40% of faculty say they are “more” or “much more” likely to do so. In contrast, only 5% were “less” or “much less” likely to do so. Broadly, roughly a quarter of MIT faculty say they are “very” or “extremely” likely to self-censor in meetings with administrators (26%), in departmental meetings with other faculty (24%), or in emails to students (28%).[9] And, roughly one-fifth say that they often felt they could not express their opinion because of how students (21%), faculty (19%), or the administration (18%) would respond.[10]

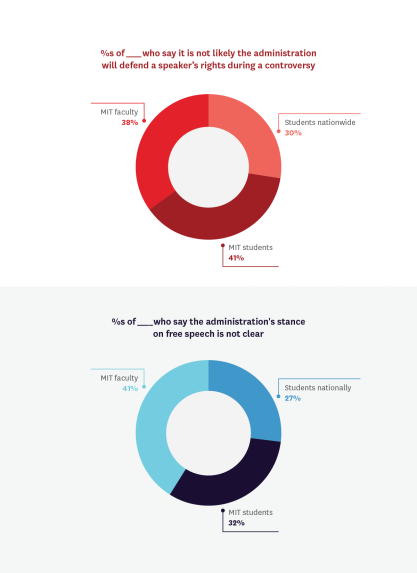

Confidence in the MIT administration’s commitment to free expression is middling at best. Almost two-in-five MIT faculty members (38%) believe it is “not very” or “not at all” likely that the administration would defend a speaker’s free speech rights if a controversy over offensive speech were to occur. In contrast, just 14% say it is “extremely” or “very” likely the administration would do so. Furthermore, just over two-in-five MIT faculty members (41%) believe it is “extremely” or “somewhat” unclear that the administration protects campus free speech, compared to 27% who believe it is “extremely” or “somewhat” clear.

Fortunately, in the time between the administration of our survey and the release of this report, the MIT faculty took matters into their own hands and adopted the concise statement from the beginning of the ad hoc working group’s longer report, which we have critiqued. Their vote sends a powerful message to the administration regarding their stance on free speech and academic freedom.

MIT students express similar concerns to faculty regarding their administration.[11] Just over four-in-ten (41%) believe it is “not very” or “not at all” likely that the administration would defend a speaker’s free speech rights if a controversy over offensive speech were to occur, compared to 17% who believe the administration is “very” or “extremely” likely to do so. Additionally, nearly one-third (32%) say that the administration’s stance on free speech is “not very” or “not at all” clear, compared to 22% who say the administration’s stance on free speech is “very” or “extremely” clear. As one student put it, after being asked to share a moment when they personally felt they could not express themselves on campus, “It seems like the administration doesn't want to hear or make change, which makes me less inclined.”

When MIT students are compared to students nationally, the picture is not pretty. Among students nationwide (N = 44,597), just under a third (30%) believe it is “not very” or “not at all” likely that the administration would defend a speaker’s free speech rights if a controversy over offensive speech were to occur. And, just over a quarter (27%) say that their administration’s stance on free speech is “not very” or “not at all” clear.

Student Attitudes Toward Free Expression

How comfortable do MIT students feel expressing themselves, compared to students nationwide?

Compared to students nationwide, MIT students are more uncomfortable expressing their views in every different campus context asked about. For instance, when comparing MIT students to students nationwide, around 10% more MIT students say they are uncomfortable “expressing disagreement with one of [their] professors about a controversial topic in a written assignment” (51% to 41%, respectively), “expressing [their] views on a controversial political topic to other students during a discussion in a common campus space, such as a quad, dining hall, or lounge” (48% to 39%, respectively), and “publicly disagreeing with a professor about a controversial topic” (68% to 60%, respectively). MIT students are also slightly more worried about expression-related reputational damage. Over two-thirds of MIT students (68%) are worried about damaging their reputations because someone misunderstands something they’ve said or done, compared to 63% of students nationwide.

Report downplays severity of self-censorship, our student survey suggests otherwise

In its report, the working group on free expression is skeptical that self-censorship is anything more than “something that (mercifully) all of us do every day” (p. 17). The group argues that “self-censorship is most often motivated not by fear of institutional retribution but by interpersonal disapproval,” thus, “we should be cautious when interpreting data and claims about campus self-censorship” (p. 18). MIT may be vindicated by our finding that just 13% of MIT students said they often feel they cannot express their opinion because of how students, a professor, or the administration would respond, compared to 22% of students nationwide.

However, when asked to share a moment when they felt they could not express their opinion on campus, MIT students said the following:

“I never feel free to express my opinion on campus. While it is likely that no official action will ever be taken against me due to the expression of my opinions, other people are quick to entirely judge others based upon a single controversial opinion these days and therefore the free expression of opinions is very dangerous and can ruin a person’s future.”

“I never feel like I can express my views around my classmates, even a lot of my close friends. They frequently talk about how evil all conservatives are and even talk about how they’d wish they'd all just die.”

“I had a hot take in my dorm lounge, and I wanted to express my disagreement without fully getting into a long conversation defending my views. I instead said I would like to have a more in-depth conversation at a later point (when not as busy), but I just got my character attacked instead.”

“I never express my religious identity and views, or my identity and struggles with gender, sexuality, and race with MIT people as a group, only with trusted individuals in contexts far removed from academics and campus culture. For me as a centrist, biracial, bisexual, gender nonconforming individual who is also a member of the Church of Jesus Christ, it is just not worth having to defend myself. I don’t want to field questions and have to speak for my religion or my identity/identity group, and I refuse to let myself become invalidated by people who happen to be loud and pushy. As individual students and professors MIT people are willing to deal with complexity and offer patience, but as a group people are all afraid of one another, so they either create an awkward atmosphere by saying nothing and assuming everything, or a confrontational atmosphere by questioning and opposing everything without affirming. In my comedy class we discussed very complex and interesting gender subversions and I wanted to participate, but knew it just wouldn't make me feel secure. I would feel judged.”

It is difficult to have an open and honest conversation about affirmative action at MIT

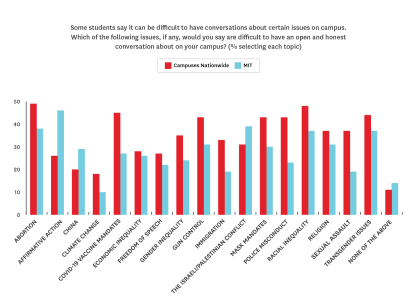

It is noteworthy that MIT students express greater difficulty having conversations about the issue of affirmative action than about any other issue. Specifically, 46% identify it as a topic that is difficult to have an open and honest conversation about on campus — a 20-point gap from the difficulty students report nationwide (26%). As one student put it, after being asked to share a moment when they personally felt they could not express themselves on campus, “Affirmative action/race based admissions is fairly controversial.” The administration’s decision to cancel Dorian Abbot’s Carlson Lecture due to his views about affirmative action and other DEI initiatives may make it even more difficult for MIT students to discuss this topic without fear of repercussions than it is for students nationwide.

Support for illiberal protest tactics is high

One of the more alarming findings from our student data is that compared to students nationwide, MIT students find it more acceptable for students to engage in all of the censorial and/or illegal speech-suppression tactics we ask about. This includes 77% of them saying that shouting down a speaker or trying to prevent them from speaking on campus is acceptable to some degree, compared to 62% of students nationwide; 52% saying that blocking other students from attending a campus speech is acceptable to some degree, compared to 37% of students nationwide; and 35% saying that using violence to stop a campus speech is acceptable to some degree, compared to 20% of students nationwide.

Faculty nationwide are less accepting of such illiberal protest tactics.[12] Less than half of faculty (45%) say that shouting down a speaker or trying to prevent them from speaking on campus is acceptable to some degree; 20% say that students blocking other students from attending a campus speech is acceptable to some degree; and, 8% say that using violence to stop a campus speech is acceptable to some degree.

Tenure Erosion and Academic Freedom

Nationwide, of every category of instructional staff, the number of tenured/tenure-track faculty has seen the smallest increase. Among all 2,439 public four-year and private not-for-profit four-year degree-granting institutions receiving federal funding, the number of full-time tenured/tenure-track faculty employed increased just 3% from 2012-2020, whereas full-time instructional staff without status increased 28% in that same time period.

The instructional staff trends at MIT track with trends seen at institutions across the country. From 2006-2020,[13] the number of full-time tenure-status faculty at MIT increased by 10% while the number of full-time instructional staff without status increased by 38%. When more detailed reporting became available in 2012, the number of tenure-track faculty still saw the smallest growth among all instructional staff categories (5% growth in full-time tenure status faculty, 40% growth in full-time instructional staff without status, 17% growth in part-time no-status faculty, and 20% growth in graduate assistants).

Meanwhile, undergraduate enrollment at MIT has largely stayed the same since 2006 (hovering around 4,300 full-time undergraduates), demonstrating a disproportionately large growth of full-time faculty without status, and a disproportionately small growth of full-time faculty with tenure status, compared to enrollment growth.

Breakdown of change in instructional staff at MIT and peer institutions

| Years: 2012-2020 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | California Institute of Technology | Georgia Institute of Technology | University of California, Berkeley | Ivy League (average of 8) | California Polytechnic State University-San Luis Obispo | Stanford University |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % change in full time faculty with tenure status | 4.69% | 7.67% | -7.28% | 4.92% | 5.69% | 10.53% | 9.53% |

| % change in part time faculty with tenure status | 9.09% | N/A | -83.33% | 14.81% | -1.49% | 14.71% | -64.29% |

| % change in full time faculty without status | 40.32% | 20.00% | 95.14% | 70.61% | 28.26% | 65.87% | -18.67% |

| % change in part time faculty without status | 16.67% | 55.00% | 75.64% | 26.53% | -4.99% | 24.19% | -2.78% |

| % change in graduate teaching assistants | 19.90% | -20.63% | 57.20% | 28.68% | 21.83%* | -14.00% | -5.68% |

The importance of tenure lies in its function to protect academic freedom,[14] a principle crucial to fulfilling a university’s role as a producer and disseminator of truth and knowledge. The at-will firing and hiring of faculty leaves controversial, unpopular, or niche research and courses easily disposable and risky to pursue as they are no longer protected from the financial and political — or, public-image related — incentives to suppress them.

As enrollment across the country continues to rise, untenured faculty are being hired to fill course demand, posing a risk to the quality and depth of higher education. More specifically, students may only be exposed to the acceptable knowledge of the time, and professors may stick to researching mainstream, popular, or in other words, safe, ideas. There are countless examples in history when those on the fringes of society made the biggest progress. Tenure protects those who dare to wade through uncharted waters.

Recommendations

In the following section, our Policy Reform team analyzes concerning elements in MIT’s policies on murals, harassment, MITnet, and freedom of expression. For each policy, we quote the relevant excerpt(s), offer our recommended revisions (in bold, or by crossing out the sentences that abridge free speech rights), and discuss our justification for the revision(s).

Housing & Residential Services: Mural Policy

Current language

Unacceptable material includes images or language that is derogatory on the basis of race, color, sex, orientation, gender identity, religion, disability, age, genetic information, veteran status, ancestry, or national or ethnic origin.

Recommended revisions

Unacceptable material includes images or language that constitutes unlawful harassment on the basis of race, color, sex, orientation, gender identity, religion, disability, age, genetic information, veteran status, ancestry, or national or ethnic origin.

Discussion

Under First Amendment standards, speech cannot be limited by the government merely because it is found derogatory on the basis of a protected characteristic. Decades of legal precedent make clear that the First Amendment protects even hateful or derogatory expression. For example, in R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, the Supreme Court struck down an ordinance that prohibited placing on any property symbols that arouse “anger, alarm or resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or gender.”[15] In Snyder v. Phelps, the Court reiterated this principle, proclaiming:

Speech is powerful. It can stir people to action, move them to tears of both joy and sorrow, and—as it did here—inflict great pain. . . . [W]e cannot react to that pain by punishing the speaker. As a Nation we have chosen a different course—to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate.[16]

More recently, the Court again affirmed this principle in Matal v. Tam, holding unanimously that the perception that expression is “hateful” or that it “demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground” is not a sufficient basis for removing speech from the protection of the First Amendment.

Accordingly, a ban on derogatory material is impermissible at an institution that commits to protecting students’ free speech rights. The recommended changes would instead ban material that constitutes unlawful harassment on the basis of those enumerated characteristics.

MIT Policies: 9.5 Harassment

Current language

Harassment is defined as unwelcome conduct of a verbal, nonverbal or physical nature that is sufficiently severe or pervasive to create a work or academic environment that a reasonable person would consider intimidating, hostile or abusive and that adversely affects an individual’s educational, work, or living environment.

In determining whether unwelcome conduct is harassing, the Institute will examine the totality of the circumstances surrounding the conduct, including its frequency, nature and severity, the relationship between the parties and the context in which the conduct occurred. Below is a partial list of examples of conduct that would likely be considered harassing, followed by a partial list of examples that would likely not constitute harassment:

[ . . . ]

Examples of possibly harassing conduct: . . . the use of certain racial epithets;

[ . . . ]

Sexual harassment is unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature, such as unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or other verbal, nonverbal, or physical conduct of a sexual nature, when: . . . The conduct is sufficiently severe or pervasive that a reasonable person would consider it intimidating, hostile or abusive and it adversely affects an individual’s educational, work, or living environment.

A partial list of examples of conduct that might be deemed to constitute sexual harassment if sufficiently severe or pervasive include:

Examples of verbal sexual harassment may include unwelcome conduct such as sexual flirtation, advances or propositions or requests for sexual activity or dates; asking about someone else's sexual activities, fantasies, preferences, or history; discussing one’s own sexual activities, fantasies, preferences, or history; verbal abuse of a sexual nature; suggestive comments; sexually explicit jokes; turning discussions at work or in the academic environment to sexual topics; and making offensive sounds such as “wolf whistles.”

Examples of nonverbal sexual harassment may include unwelcome conduct such as displaying sexual objects, pictures or other images; invading a person's personal body space, such as standing closer than appropriate or necessary or hovering; displaying or wearing objects or items of clothing which express sexually offensive content; making sexual gestures with hands or body movements; looking at a person in a sexually suggestive or intimidating manner; or delivering unwanted letters, gifts, or other items of a sexual nature.

Recommended revisions

Harassment is defined as unwelcome conduct of a verbal, nonverbal or physical nature that is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive, and that so undermines and detracts from the victims’ educational experience, that the victim-students are effectively denied equal access to the Institute’s resources and opportunities.

In determining whether unwelcome conduct is harassing, the Institute will examine the totality of the circumstances surrounding the conduct, including its frequency, nature and severity, the relationship between the parties and the context in which the conduct occurred. Below is a partial list of examples of conduct that could constitute harassment if a part of a pattern of conduct that meets the standard for harassment set forth above, followed by a partial list of examples that would likely not constitute harassment:

[ . . . ]

Examples of possibly harassing conduct: . . . the use of certain racial epithets;

[ . . . ]

Sexual harassment is unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature, such as unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or other verbal, nonverbal, or physical conduct of a sexual nature, when: . . . The conduct is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive, and so undermines and detracts from the victims’ educational experience, that the victim-students are effectively denied equal access to the Institute’s resources and opportunities.

A partial list of examples of conduct that might be deemed to constitute sexual harassment when they are a part of a pattern of conduct meeting the standard for sexual harassment set forth above include:

Examples of verbal sexual harassment may include unwelcome conduct such as sexual flirtation, advances or propositions or requests for sexual activity or dates; asking about someone else's sexual activities, fantasies, preferences, or history; discussing one’s own sexual activities, fantasies, preferences, or history; verbal abuse of a sexual nature; suggestive comments; sexually explicit jokes; turning discussions at work or in the academic environment to sexual topics; and making offensive sounds such as “wolf whistles.”

Examples of nonverbal sexual harassment may include unwelcome conduct such as displaying sexual objects, pictures or other images; invading a person's personal body space, such as standing closer than appropriate or necessary or hovering; displaying or wearing objects or items of clothing which express sexually offensive content; making sexual gestures with hands or body movements; looking at a person in a sexually suggestive or intimidating manner; or delivering unwanted letters, gifts, or other items of a sexual nature.

Discussion

Under the standard for student-on-student (or peer) harassment provided by the Supreme Court in Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, alleged harassment must be “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive, and that so undermines and detracts from the victims’ educational experience, that the victim-students are effectively denied equal access to an institution’s resources and opportunities.”[19] As the Court’s only decision to-date regarding the substantive standard for peer harassment in education, Davis is controlling on this issue.

In contrast, this policy’s definitions of harassment and sexual harassment only require that conduct is severe or pervasive, rather than requiring both severe and pervasive conduct per the Court’s standard from Davis. This “severe or pervasive” language may be in place in this policy because this is the standard applicable to employment discrimination under Title VII. However, this workplace standard is inapplicable to peer harassment in the educational setting. Accordingly, MIT should regulate student-on-student and other harassment separately in order to reflect these different legal standards.

Additionally, the policy provides lists of examples of conduct that may constitute either harassment or sexual harassment. It is reasonable for the Institute to provide examples of conduct that may be a part of harassment for illustrative purposes, but the way these examples are introduced may suggest to students that they are prohibited across the board. The recommended revisions would adjust the policy to make clear these examples must be a part of conduct that reaches the standard for harassment in order to be punishable.

MITNet Rules of Use

Current language

Any use that might contribute to the creation of a hostile academic or work environment is prohibited

[ . . . ]

Recommended revisions

Any use that constitutes hostile academic or work environment harassment is prohibited . . .

Discussion

By prohibiting any use that might contribute to the creation of a hostile academic environment, this policy allows administrators to sanction speech they subjectively find could potentially create a hostile environment but that does not actually constitute unlawful harassment. As a result, speech that is protected under First Amendment standards may too easily be limited by the administration.

The recommended revisions would instead ban only any use of MITNet that constitutes hostile environment harassment.

Mind and Hand Book: Policies Regarding Student Behavior — II (10) Freedom of Expression

Current language

Freedom of expression is essential to the mission of a university. So is freedom from unreasonable and disruptive offense. Members of this educational community are encouraged to avoid putting these essential elements of our university to a balancing test.

Recommended Revisions

Freedom of expression is essential to the mission of a university.

Discussion

By stating that “freedom from unreasonable and disruptive offense” is essential to the mission of a university and discouraging students from pitting this freedom against freedom of expression, this policy risks producing a chilling effect on speech protected under First Amendment standards.

The policy indicates to students that administrators will be weighing students’ free speech against the interest of avoiding “disruptive offense,” and may infringe on protected speech in order to prevent such offense. The recommended revisions remove the portion of the policy that suggests that students’ freedom of expression will be compromised by other values, leaving the remainder of the policy, which encourages students to respond to speech they dislike with their own speech.

Conclusion

MIT has an exceptional academic reputation, but a mediocre climate for free speech and inquiry. It is only a matter of time before the former is compromised by the latter.

MIT students exhibit worrying signs of intolerance, are afraid to express their views (particularly on affirmative action), and are not highly confident that the administration values free expression. MIT faculty are increasingly afraid to express their views, are not highly confident that the administration values free speech, and do not believe the administration should sanction professors for opposing diversity, equity, and inclusion policies.

MIT can create a healthier climate for free expression by taking the following steps:

- Implementing the series of policy revisions recommended by FIRE’s Policy Reform team.

- Following MIT faculty’s lead by formally adopting the MIT Statement on Freedom of Expression and Academic Freedom as the guiding principle behind President Sally Kornbluth’s administration..

- Offering a freshmen orientation that educates incoming students about the history and value of free speech in the country.

- Eliminating its mandatory diversity statements for faculty applicants.

Notes

[1]Heilman, M. (1994). Affirmative action: Some unintended consequences for working women. In Research in organizational behavior (pp. 125-169). JAI Press; Heilman, M. E., Simon, M. C., & Repper, D. P. (1987). Intentionally favored, unintentionally harmed? Impact of sex-based preferential selection on self-perceptions and self-evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(1), 62.

[2]Niemann, Y. F., & Dovidio, J. F. (2005). Affirmative action and job satisfaction: Understanding underlying processes. Journal of Social Issues, 61(3), 507-523.

[3]Heilman, M. E., & Alcott, V. B. (2001). What I think you think of me: Women's reactions to being viewed as beneficiaries of preferential selection. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), 574.

[4]Major, B., & O'brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual review of psychology, 56(1), 393-421; Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 379-440). Academic Press.

[5]Kaplan, S., Bradley, J. C., Luchman, J. N., & Haynes, D. (2009). On the role of positive and negative affectivity in job performance: a meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Applied psychology, 94(1), 162; Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Forbes, C. (2008). An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological review, 115(2), 336.

[6] Kaufmann, E. (2021). Academic freedom in crisis: Punishment, political discrimination, and self-censorship. Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology. Available online: https://cspicenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/AcademicFreedom.pdf; Peters, U., Honeycutt, N., De Block, A., & Jussim, L. (2020). Ideological diversity, hostility, and discrimination in philosophy. Philosophical Psychology, 33(4), 511-548.

[7] Holbrook, A., Krosnick, J., & Pfent, A. (2007). The causes and consequences of response rates in surveys by the news media and government contractor survey research firms. In J.M. Lepkowski, N. C. Tucker, J. M. Brick, E. D. De Leeuw, L. Japec, P. J. Lavrakas, et al (Eds.), Advances in telephone survey methodology. Wiley; Templeton, L., Deehan, A., Taylor, C., Drummond, C., & Strang, J. (1997). Surveying general practitioners: Does a low response rate matter? British Journal of General Practice, 47(415), 91–94.

[8] Additionally, roughly one-third didn’t know enough about the matter to provide an opinion (19%) or gave no response (13%).

[9]Self-censorship was defined as: Refraining from sharing certain views because you fear social (e.g., exclusion from social events), professional (e.g., losing job or promotion), legal (e.g., prosecution or fine), or violent (e.g., assault) consequences, whether in-person or remotely (e.g., by phone or online), and whether the consequences come from state or non-state sources.

[10]“Often” represents the sum of the percentage of faculty who said they felt this way “fairly often, a couple times a week” or that they felt this way “very often, nearly every day.”

[11]All student data comes from FIRE’s 2022 Campus Free Speech Rankings survey. The total number of MIT students surveyed was 250 and the total number of students surveyed nationwide was 44,847. All data from MIT students is weighted by demographic information supplied by MIT to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) database: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data.

[12] Nationwide faculty data comes from a survey administered by FIRE and Social Science Research Services (SSRS) this past summer. The total number of faculty surveyed was 1,491.

[13] While there is data available from 1987, for some schools (it doesn’t seem to be the case for MIT), the numbers fluctuate a lot. Starting in 2002, tenure statistics became mandatory, and then merged with other surveys in 2006. Although the MIT numbers before 2006 are not wildly unreasonable, the inconsistencies in other schools suggests that the reporting in general on these statistics are unreliable. The data were collected using this IPEDS tool. For 2012-2020 data, the following variables were selected: Full-and part-time medical and non-medical staff by occupational category, faculty and tenure status>New HR occupational categories based on SOC 2010>Fall 2020-2012>Instructional staff, total (Tenured, On Tenure Track, Not on Tenure Track/No Tenure System, Without faculty status)>Graduate assistants, Total (Teaching)>Full-time employees (excluding medical schools), Part-time employees (excluding medical schools). For 2011-2006 data, the following variables were selected: Tenure status of full-time non-medical instructional staff in 4-year institutions, by contract length, gender, and academic rank: Academic year 2006-07 to 2011-12 > Academic year 2006-07 to 2011-12> Years 2012-2006>(Tenured, men), (On tenure track, men), (Not on tenure track/no tenure system, men), (Without faculty status, men), (Tenured, women), (On tenure track, women), (Not on tenure track/no tenure system, women), (Without faculty status, women). *University of Pennsylvania was excluded from this average due to incomplete data reporting. They reported the following figures for graduate teaching assistants: 2020 (0), 2019 (0), 2018 (1), 2017 (3), 2016 (1), 2015 (0), 2014 (4), 2013 (2), 2012 (6).

[14] Brown, R. S., & Kurland, J. E. (1990). Academic Tenure and Academic Freedom. Law and Contemporary Problems, 53(3), 325–355. https://doi.org/10.2307/1191800

[15]505 U.S. 377 (1992).

[16] 562 U.S. 443, 461 (2011).

[17] 137 S. Ct. 1744, 1764 (2017).

[18] Note that the language of this policy is duplicated in the Mind and Hand Book: Policies Regarding Student Behavior - II (7) (D) (2) “Sexual Harassment.” The recommended changes apply to both policies.

[19] 526 U.S. 629, 651 (1999).

Appendix

Q: How clear is it to you that your college administration protects free speech on campus?

| Response | Students Nationally | MIT Students | MIT Faculty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all clear* | 8% | 6% | 22% |

| Not very clear* | 19% | 26% | 19% |

| Somewhat clear* | 42% | 46% | 24% |

| Very clear | 22% | 18% | 16% |

| Extremely clear | 9% | 4% | 11% |

| * = “Extremely unclear,” “somewhat unclear,” and “neither clear nor unclear” were the response options for the MIT faculty survey. | |||

Q: If a controversy over offensive speech were to occur on your campus, how likely is it that the administration would defend the speaker's right to express their views?

| Response | Students Nationally | MIT Students | MIT Faculty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all likely | 7% | 4% | 14% |

| Not very likely | 22% | 37% | 24% |

| Somewhat likely | 47% | 42% | 28% |

| Very likely | 17% | 16% | 10% |

| Extremely likely | 6% | 1% | 4% |

Q: How comfortable would you feel doing the following on your campus?

| Publicly disagreeing with a professor about a controversial topic. | USA | MIT |

|---|---|---|

| Very comfortable | 13% | 11% |

| Somewhat comfortable | 28% | 21% |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 34% | 41% |

| Very uncomfortable | 25% | 28% |

| % Comfortable | 40% | 32% |

| % Uncomfortable | 60% | 68% |

| Expressing disagreement with one of your professors about a controversial topic in a written assignment. | USA | MIT |

|---|---|---|

| Very comfortable | 20% | 16% |

| Somewhat comfortable | 39% | 32% |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 28% | 37% |

| Very uncomfortable | 13% | 15% |

| % Comfortable | 59% | 49% |

| % Uncomfortable | 41% | 51% |

| Expressing your views on a controversial political topic during an in-class discussion. | USA | MIT |

|---|---|---|

| Very comfortable | 17% | 11% |

| Somewhat comfortable | 35% | 36% |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 29% | 34% |

| Very uncomfortable | 19% | 19% |

| % Comfortable | 52% | 48% |

| % Uncomfortable | 48% | 52% |

| Expressing your views on a controversial political topic to other students during a discussion in a common campus space, such as a quad, dining hall, or lounge. | USA | MIT |

|---|---|---|

| Very comfortable | 22% | 21% |

| Somewhat comfortable | 39% | 32% |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 26% | 33% |

| Very uncomfortable | 13% | 14% |

| % Comfortable | 61% | 52% |

| % Uncomfortable | 39% | 48% |

| Expressing an unpopular opinion to your fellow students on a social media account tied to your name. | USA | MIT |

|---|---|---|

| Very comfortable | 14% | 8% |

| Somewhat comfortable | 26% | 26% |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 32% | 30% |

| Very uncomfortable | 29% | 36% |

| % Comfortable | 40% | 34% |

| % Uncomfortable | 60% | 66% |

Q: Which of the following most accurately captures your view on the cancellation of Dorian Abbot’s John Carlson Lecture?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| The Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences was right to cancel Abbot’s John Carlson Lecture. | 16% |

| The Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences was wrong to cancel Abbot’s John Carlson Lecture. | 52% |

| Don’t know enough about the matter to provide an opinion. | 19% |

| No answer | 13% |

Q: Some universities ask applicants for faculty positions to submit statements demonstrating their commitment to equity and diversity before they can be considered for a job. Which comes closer to your view?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response | % of faculty in 2022 Faculty Study giving response* |

|---|---|---|

| This is a justifiable requirement for a job at a university. | 37% | 50% |

| This is an ideological litmus test that violates academic freedom. | 46% | 50% |

| No answer | 16% | <1% |

Q: An MIT professor writes an op ed in a national news outlet that criticizes university efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion on campus. A group of students start a petition demanding the administration fire the professor. What is the appropriate administrative response?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| The administration should defend the professor’s free speech rights. | 63% |

| The administration should condemn the professor’s speech, but not punish the professor. | 18% |

| The administration should conduct a formal investigation into the incident. | 6% |

| The administration should remove the professor from the classroom. | 0% |

| The administration should suspend the professor. | 0% |

| The administration should terminate the professor. | 0% |

| No answer | 13% |

Q: If several professors refused to take mandatory diversity training at your college or university, claiming that the training is hostile to their identity, how should the administration deal with them?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response | % of faculty in 2022 Faculty Study giving response |

|---|---|---|

| No action of any kind should be taken. | 28% | 43% |

| No formal disincentives should be issued.* | 32% | 24% |

| The professors should lose opportunities at work.* | 12% | 15% |

| The professors should be suspended until they comply. | 7% | 14% |

| The professors should be fired. | 1% | 3% |

| No answer | 20% | 1% |

| *response options differed slightly in the 2022 Faculty Study. Instead of “No formal disincentives should be issued,” was, “Do not issue any formal disincentives but apply social and professional pressure.” And instead of “The professors should lose opportunities at work,” was, “The professors should be removed from the classroom until they comply.” | ||

Q: On your campus, how often, if at all, have you felt that you could not express your opinion on a subject because of how students would respond?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| Never | 22% |

| Rarely | 27% |

| Occasionally | 30% |

| Fairly often, a couple times a week | 12% |

| Very often, nearly every day | 9% |

Q: … What about how your colleagues would respond?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| Never | 19% |

| Rarely | 28% |

| Occasionally | 33% |

| Fairly often, a couple times a week | 12% |

| Very often, nearly every day | 7% |

Q: … And what about how administrators would respond?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| Never | 28% |

| Rarely | 21% |

| Occasionally | 32% |

| Fairly often, a couple times a week | 10% |

| Very often, nearly every day | 8% |

This next series of questions asks you about self-censorship in different settings. For the purpose of these questions, self-censorship is defined as:

Refraining from sharing certain views because you fear social (e.g., exclusion from social events), professional (e.g., losing a job or promotion), legal (e.g., prosecution or fine), or violent (e.g., assault) consequences, whether in-person or remotely (e.g., by phone or online), and whether the consequences come from state or non-state sources.

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| Not at all likely | 16% |

| Not very likely | 22% |

| Somewhat likely | 26% |

| Very likely | 12% |

| Extremely likely | 14% |

Q: So, how likely, if at all, are you to self-censor in departmental meetings with other faculty?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| Not at all likely | 17% |

| Not very likely | 25% |

| Somewhat likely | 25% |

| Very likely | 12% |

| Extremely likely | 12% |

Q: So, how likely, if at all, are you to self-censor in emails to other faculty?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| Not at all likely | 13% |

| Not very likely | 26% |

| Somewhat likely | 27% |

| Very likely | 13% |

| Extremely likely | 10% |

Q: So, how likely, if at all, are you to self-censor in emails to your students?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| Not at all likely | 13% |

| Not very likely | 19% |

| Somewhat likely | 26% |

| Very likely | 17% |

| Extremely likely | 11% |

Q: So, how likely, if at all, are you to self-censor in social media posts?

| Response | % of MIT faculty giving response |

|---|---|

| Not at all likely | 17% |

| Not very likely | 11% |

| Somewhat likely | 13% |

| Very likely | 13% |

| Extremely likely | 27% |

The following tables show how students nationwide compare to MIT students.

Q: How acceptable would you say it is for students to engage in the following action to protest a campus speaker?

| Shouting down a speaker or trying to prevent them from speaking on campus. | USA | MIT |

|---|---|---|

| Always acceptable | 5% | 5% |

| Sometimes acceptable | 25% | 39% |

| Rarely acceptable | 32% | 34% |

| Never acceptable | 38% | 23% |

| % Acceptable | 62% | 77% |

| Blocking other students from attending a campus speech. | USA | MIT |

|---|---|---|

| Always acceptable | 2% | 2% |

| Sometimes acceptable | 10% | 10% |

| Rarely acceptable | 25% | 39% |

| Never acceptable | 63% | 49% |

| % Acceptable | 37% | 52% |

| Using violence to stop a campus speech. | USA | MIT |

|---|---|---|

| Always acceptable | 1% | 1% |

| Sometimes acceptable | 4% | 4% |

| Rarely acceptable | 15% | 30% |

| Never acceptable | 80% | 66% |

| % Acceptable | 20% | 35% |